Preface

“Life in the Letters: From Nokta-i Suğra to Kufi Legacy”

I am going to articulate my ideas about Kufi scripture because I wish to present my Kufi calligraphy compositions collectively; so that they may be preserved and registered in a book format. Besides, being a history professor—my doctoral dissertation was on “Arab Invasions to Anatolia (640-750 A.D.)”—I am also recognized as a Kufi calligrapher, professionally accepting orders and composing Kufi calligraphy since 1970. My first design, “Nokta-i Suğra,” was published on the cover of a book, Peyami Safa’s Sanat, Edebiyat Tenkit, Ötüken Publishing, Istanbul, 1970.

This Nokta design is cited and published in the article “Nokta-i Suğrâ” in the Encyclopedia of Literature (Edebiyat Ansiklopedisi), published by Dergah.yy, İstanbul, 1991.

- Personal journey as a calligrapher and historian

- Origins of your artistic and academic engagement with Kufi

While working as a high school teacher, in 1973, I created my Kufi composition featuring the names of Allah, Muhammad, and the four caliphs for a book cover (Hadislerle Müslümanlık),

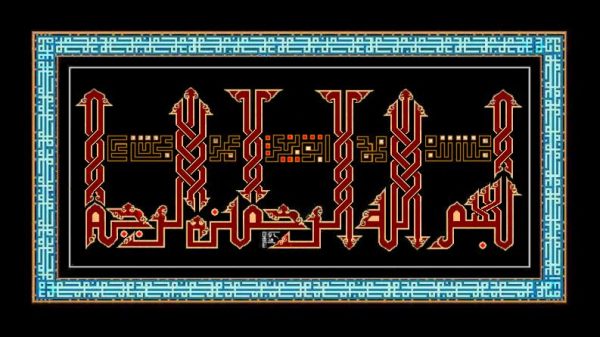

and my Kufi Besmele design for Aydın Bolak in 1974.

It was because of that Besmele design, which was discovered by chance in Enderun Sahafiye by Prof. Dr. Kaya Bilgegil, that I was appointed as a calligraphy artist and specialist in paleography and epigraphy. Thus, my university career began as a calligraphy artist in the Department of Turkish Literature in 1976, and just one year later, I was employed in the History Department of Atatürk University.

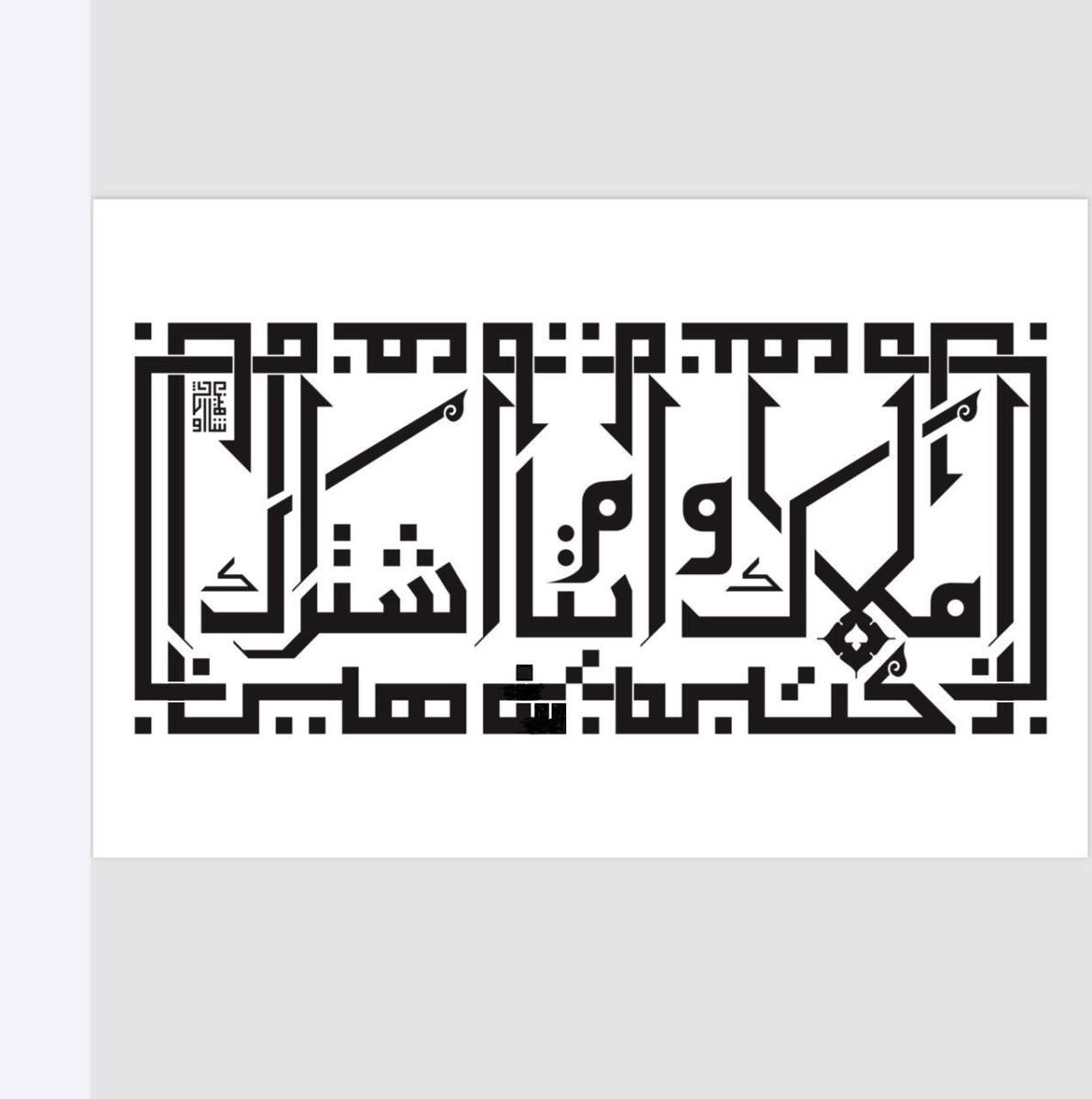

In April 2024, I created a new Kufi composition in response to a request, and this recent work inspired me to revisit and revise some of my earlier Kufi sketches.

Now, as a retired history professor, I have decided to showcase all of my Kufi calligraphy compositions in book form and to write about the history of Kufi scripture more broadly. I see this as a new opportunity to convey all of my ideas once again—perhaps more clearly than in my previous writings—illuminated by the profound light of the Kufi scripture. For this reason, I intend to offer some brief critiques on language and human knowledge in general before delving into the history of Kufi calligraphy. I will attempt to interpret the history of Kufi scripture within the framework of my own philosophy of history; adopting a holistic and multidisciplinary approach—that is, considering all the varied angles and perspectives employed by diverse disciplines. Let me state here that “all meaning is an angle,” and understanding cannot exist without perspective.

On the other hand, due to the special significance of language and the sacred scripture Qur’an in Islam, Kufi scripture may be debated from theological and semantic standpoints, since some linguists hold that language is God-given and not created by humans.

Indeed, Kufi script has been used primarily for writing the Qur’an for centuries, yet it is found everywhere—from buildings to instruments and even on clothing. Calligraphic writing has been the most formative element of Islamic culture, to the extent that it is the most distinctive and visible aspect of Islamic civilization. From the 7th to the 11th century, for five centuries, Kufic calligraphy was the most prominent feature of the cultural identity of the Muslim world, manifesting as a civilization of Kufi scripture. Consequently, Quranic verses were visible everywhere—from architecture to the ‘tiraz’ garments. The word of God, seemingly embodied by the Kufic calligraphy, as if it were the incarnation of the sacred “Kelam” (akin to the ‘Logos’ concept of Heraclitus or the incarnation of the word of God in flesh by Jesus)—was embodied and represented by the solemn character of the Kufi scripture of the Qur’an. It permeated every aspect of Islamic culture, everywhere. This brings to mind a verse from the Qur’an: “Ve lillâhi’l-maşrıku ve’l-mağrib. Fe’eynemâ tuvellû fe-semme vechullah”: “To God belong the East and the West; whithersoever you turn, there is the Face of God…”