Kemal Batanay hocam, Nasreddin hocanın bu hikayesindeki gibi yapmış, önce tanbur dersi için benden ayda 40 lira almış, 2 ay sonra : “Anlaşılan devam edeceksin, artık para vermene lüzum yok” demişti. 🙂 🙂 🙂 🙂

Hodja wanted to learn to play the lute. So he approached a music teacher and asked him, “How much do you charge for private lute lessons?” “Three silvers pieces for the first month; then after that, one silver piece a month.” “Oh, that’s very fair,” exclamied Hodja. “I’ll start with the second month.”

Autuph Cahalil— Sufi Tale (Essential Sufism, p. 165).

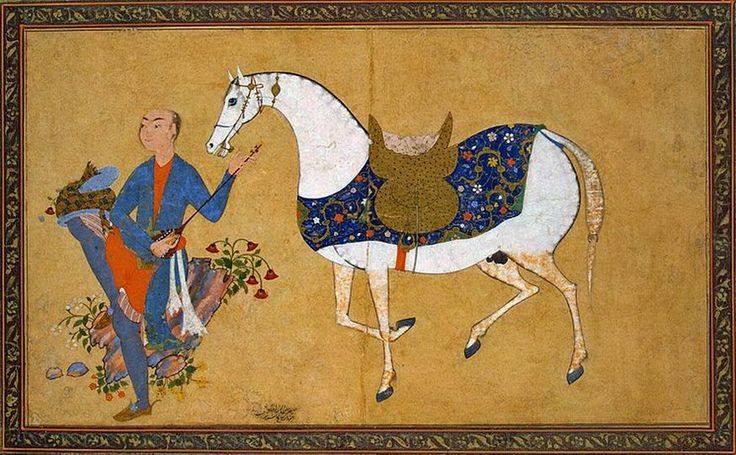

http://totallyhistory.com/art-history/

nuri arlasez ve raif yelkenci

Nuri Arlasez röportajı için link.

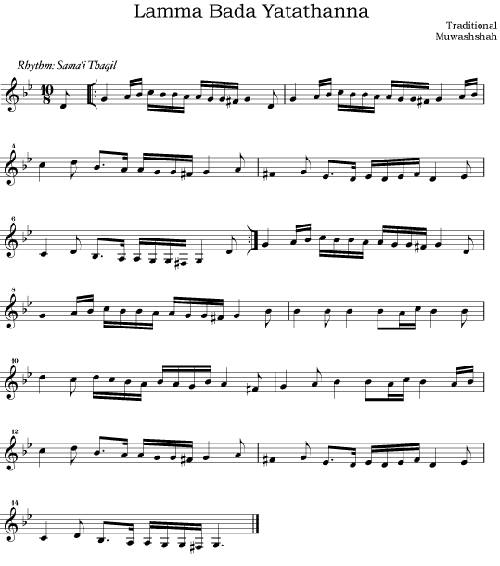

لما بدا يتثنى قضى الصبا و الدلال حبي جمال فتنا أفديه هل من وصال أومى بلحظ أسرنا بالروض بين التلال غصن سبا حينما غنى هواه و مال وعدي و يا حيرتي …. ما لي رحيم شكوتي بالحب من لوعتي إلا مليك الجمال

Lamma Bada” çok eskilerden gelen bir Endülüs şarkısıdır.1960 yılında Fairuz tarafından bir kuyumcu titizliğiyle derlenip Suriye’nin Bilād eş-Şam (Damascus) festivalinde Arap alemine hediye edilmiştir,onlarca şarkıcı tarafından seslendirilmiştir… O ,sallana sallana yürümeye başladığında aman aman aman aman Onun güzelliği,cemali beni hayretlere sürükler aman aman aman aman Ben gözlerinin esiri haline gelmişim aman aman aman aman O eğilince zaman durur aman aman aman aman Ey söz, Ey benim şaşkınlıklarım kim benim şikayetime cevap verebilir aşk ve acı hakkında,sevgim ve tutkularım hakkında ama o güzel melek mi (verecek)? aman aman aman aman aşk ve acı hakkında,sevgim ve tutkularım hakkında ama o güzel melek mi (verecek)? aman aman aman aman Çeviri:Antioche Orantes (2001)

….

When she began to sway, her beauty amazed me. Surrender Surrender .She imprisoned me with a glance. She was a swaying branch that consumed me .Surrender Surrender. Surrender Surrender Oh my destiny, my confusion, No one can comfort me in my misery, In my lamenting and suffering for love, But for the one in the beautiful mirage; My beloved’s beauty drives me to distraction, Surrender Surrender

THE ARAB MUWASHSHAH AND ZAJAL POETRY AND THEIR INFLUENCE ON EUROPEAN MUSIC AND SONG

by Habeeb Salloum

For a month I had explored Agadir, Morocco’s ‘Queen of Resorts’, and its many touristic pleasures. Yet, I was not content. My search for the enchanting musical evenings of Moorish Spain, which were carried to North Africa by the Muslims expelled from their Iberian Peninsula paradise, had been unsuccessful. “What has happened to themuwashshah and zajal poetry developed in Al-Andalus (the Spain of the Arabs) and set to song?” I often wondered as I pursued my goal in vain.

Night after night I explored the entertainment spots and sampled Moroccan television, but the merrymaking of the Spanish Arabs was nowhere to be found. Instead, for diversion, the hotels and clubs offered the music and songs of the Berbers and television usually featured French and, at times, poor Egyptian movies. The pastime of the 20th century had overwhelmed the captivating past.

During my last Saturday evening in Agadir, when I turned on the television, I had given up the notion of ever seeing the muwashshah orzajal. Suddenly, I sat up excited. The program for that night was to be provided live by the Andalusian ensemble in the northern Moroccan city of Oujda.

The camera zoomed in on an orchestra of, perhaps, fifty men and women attired in colourfully rich Moroccan dress. Their drums, lutes,kamanjahs and other bowed-stringed instruments were a replica of those once played in the palaces of Moorish Spain. Beautiful women alternated with men in singing verses of poetry. At other times, a man or woman would sing a phrase which would be answered by the entire group. I was entranced, and in my fantasy I was back in Arab Cordova when it was the capital of Muslim Spain – known to many of the world’s inhabitants as the `jewel of the world’.

I could not believe my ears. The enticing voice of one of the women singers was pouring out the words of the great 14th century Arab Andalusian statesman and muwashshah poet par excellence, Ibn al-Khatib. He composed the verse being sung after, with the exception of Granada, all of Spain had been lost to the Christians.

“Generous are the clouds, if they should shed tears

For the past ages which link us to Andalusia.

This link can now be only in a dream which cheers,

In sleep, or in a fleeting deceit or idea”.

It was beautiful poetry sung by a bewitching voice which seduced my very soul.

Like my fascination with this type of revelry, for centuries the Arabs in the Iberian Peninsula were attracted to the muwashshah and zajal – their creation of these two forms of Hispano-Arab poetry put to music and song. They were, indisputably, the original contribution of Muslim Spain to Arab verse, and were to bequeath a rich legacy to European medieval popular entertainment.

The muwashshah and zajal type songs have their roots in the Arab East and North Africa, but were developed in Al-Andalus. When the Arabs moved westward into North Africa they found a music which differed very little from their own. Some historians even believe that the pre-Islamic music in that part of the world came in the mist of history from the Arabian Peninsula – carried by the Arab tribes migrating throughout the centuries to North Africa.

During their first years in Spain and Portugal, the Arabs did not alter in any way the music and song of their ancestors. Musicians and singers came on a continual basis from the East and, in the furthest west of the Arab Empire, found a welcoming land.

The most famous of these was Ziryab, one of the greatest teachers of musicians and singers of all times. He arrived in Andalusia in 821 A.D. and enchanted the court of Cordova for years with his wit, music and song. His method of teaching students how to sing, even today, has its pupils. Ziryab was steeped in the knowledge of refined music learned in Bagdhad – the world’s leading intellectual and cultural city in that era. This, no doubt, aided in his establishing the first conservatory of music in Cordova and later others in the larger centres of Muslim Spain. A few decades after Ziryab arrived to the Iberian Peninsula, something new happened in the world of Andalusian music and song. In the southern Spanish town of Cabra was born the blind poet and singer Muqaddam Ibn Mu afa al-Qabri – the creator of themuwashshahat. Even though Ibn Bassam, an Arab-Spanish author of the 12th century, states that the inventor was Muhammad Ibn Mahmud al- Umari al-Darir, the most commonly held view is that of the 14th century historian, Ibn Khaldun, who asserts that this poetry was the brain child of Muqaddam.

A blind poet, he is credited by almost all historians with being the architect of the muwashshah and its vernacular form, zajal. On the other hand, a number of music researchers trace zajal back to the famous Moorish philosopher and musician of Zaragoza, Ibn Bajja, known to the West as Avempace, who in his poetry abandoned classical Arabic for the colloquial.

During the 11th and 12th centuries, muwashshah and zajal verse reached their peak of perfection in Moorish Spain. In this period, first under the tawa’if (petty states), then the subsequent Almoravid and Almohad dynasties, both these forms of music and song enjoyed a great vogue and were incorporated into the Arab/Islamic art of entertainment.

After the Muslims were expelled from the Iberian Peninsula, the poets of the muwashshah and zajal were dispersed throughout the Arab world and, eventually, their art became popular in every Muslim country. In the Arab world of today, especially in North Africa, themuwashshah which is a more artistic production than the zajal,besides being performed live, is often heard on radio and television. More the common man’s diversion, zajal also still has its devoted fans in a number of Arab countries, especially Lebanon where this form of spontaneous song draws crowds from all walks of life.

The muwashsha , whose name is derived from the Arabic noun washah(jewelled sash worn diagonally from shoulder to waist), was, and still is, written in classical Arabic, apart from the clinching couplet calledkharja. This concluding verse, in Moorish Spain, was in vulgar Arabic or in one of the Romance languages found at that time in the Iberian Peninsula. It usually summarized the whole meaning and inspiration of the poem.

The muwashshah consists of three line stanzas with a recurring rhyme, introduced at the beginning. A strophic form, its rhymes can change from one verse to the next – a departure from the usual Arabic poetry which had a single rhyme for the entire poem.

Each section of the poem is complete or autonomous in itself, engirdled by the refrain. It is said that the interwoven rhymes of themuwashshah represent the exact auditory – rhythmic counterpart of the interlacing arches in the Great Mosque of Cordova. L.I. al-Faruqi in her article in the magazine Ethnomusicology writes that themuwashshah is an embodiment of Islamic culture’s specialty in the non-developmental form – a disjunct arabesque with many centres of tension, many successive parts, each as important as every other one.

The themes include asceticism, courage, description of nature, elegy, praise, pride, religion, satire, wine, and eroticism or, as often is the case, love-lament – themes not much different than those found in pre-Islamic Arabia. They are vocal compositions performed by a chorus or by a chorus alternating with a soloist, always following the traditional style.

The zajal is vernacular verse which developed from the muwashshahat– some say it is the oldest form of the muwashshah. A popular form of entertainment, it was composed entirely in the local tongues of the Iberian Peninsula. Zajal reached its culmination of perfection under the adventurer and famous Cordovan poet Ibn Quzman, l080 – 1160 A.D. – in any language, one of the foremost poets of the Middle Ages. Quzman used to boast that his zajal was sung as far away as the eastern Arab world. The greatest composer of this type of poetry, he wrote a book which included 150 zajaIs, full of love, wine and the other joys of life. Still in existence, it gives a clear insight of the people’s songs in Arab Spain.

Zajal is a spontaneous form of short poems of whatever comes to a performer’s mind. The poet plays with different themes and weaves them in and out of the current of the verse. It is often sung in stanzas with each following a different rhyme.

A voice of the ordinary man, it is constantly ironic, often tender, at times brutal but always full of good humour. In the night spots of Lebanon, I would often listen captivated for hours as the performers satirized or praised each other in flowery phrases. In amazing original and impromptu verse, they raised or lowered the emotions of the audience as had the Arab zajal poets in Moorish Spain.

At first, the muwashshahat and zajal, both constituting a departure from the tradition represented by classical poetry, existed side by side and often overlapped. However, in the ensuing centuries, because of the long standing Arab tradition of not writing the vernacular, a good number of muwashshahat and only a few zajals have come down to us in written form. It was thought that because of their smoothness and literary Arabic qualities, the muwashshahat were worthy of preservation. On the other hand, zajal remained on the oral level, influenced by non-Arab speech or Arabic dialects.

According to A.J. Chejne in Muslim Spain – Its History and Culture, Al-Andalus contributed the muwashshah and zajal to the body of Arabic poetry in the same manner that Arabia contributed its classical poetry. Through these two popular poetical forms, Arab Spain was able to emancipate itself from the formalism of classical verse, producing thereby a kind of poetry that was spontaneous and simple – akin to the personality and temperament of the Andalusians.

There is no question that the Moors left in the Iberian Peninsula a unique musical heritage. This added to the concept of courtly love – first practised by the Arabs – made Spain for hundreds of years a land of romance. >From the days of the Moors in Spain it has been the home of dance, music, merrymaking and the divan of love. In the villas of the nobles, in its gardens, on its river banks and in private and public places, it is said that singing and the sound of musical instruments are to be heard in all places and on every occasion.

From their citadel of entertainment, the Arabs defused their music and song to the Christian parts of the Iberian Peninsula and from there to the remainder of western Europe. Music was considered so important in Muslim Spain that, at times, a form of religious music was taught as a subject in the mosques. Ibn Khaldun states that the interest and support for music by the Arabs of Al-Andalus played a leading role in its dispersion throughout Spain and the neighbouring European countries.

Zajal, in the vulgar Arabic and the Romance tongues was sung by everyone in both Christian and Muslim Spain. Chejne contends that there is a striking similarity between zajal, and early Spanish and Provençal poetry in rhyme, theme, the number of strophes, the use of a messenger between the lover and beloved and the duty of the lover toward the beloved. He cites as an example Juan Ruiz’s El Libro de Buen Amor, known as the Arcipreste de Hita, the author’s use ofzajal is reminiscent of the model created by the Arab Andalusians.

I was reminded of how much the zajal remains part of the Latin-speaking world’s musical culture a few years ago during one of my visits to Brazil. One evening while strolling by a park in Recife, that country’s famous northeastern resort, I heard what I thought was Arab music. As I neared, I saw two men each with a tambourine, challenging each other in verse while the ringed audience cheered when one or the other made a point. I could hardly believe what I was seeing and hearing. It was no different than the zajal duels heard in the villages of Syria and Lebanon. This poetic contribution of the Arabs to the Iberian Peninsula was alive and doing well in the Portuguese-speaking world.

The kharjas of the muwashshahat, very similar to zajal, are believed to be the oldest poetic texts of any vernacular in Europe. Hence, they very well could have been the origin of lyric poetry in Romance literature. It is believed that they gave rise to the 15th century villancico, a type of Christian carol to which they bear a close resemblance, and the coplas(ballads), still found throughout the Spanish-speaking world.

Those who are familiar with Spanish music assert that from themuwashshahat and zajal the Spanish cantigas developed. In theCantigas de Santa Maria compiled by Alfonso the Wise, the musical form of the zajal is clearly evident. Some music chroniclers maintain that the majority of Alfonso’s cantigas were direct translations of Arab zajal verses.

The cantigas had an immense impact on the western medieval world. They not only influenced the songs of Spain, but also gave impetus to the evolvement of all European music.

Both the muwashshah and zajal poetry are clearly to be found in the early music and song of Europe. For centuries Arab culture exercised a strong influence on the entertainment of the southern part of that continent. E.G. Gómez writing about Moorish Spain in Islam and the Arab World indicates that the muwashshah verse is probably more interesting to westerners than to the eastern Arabs, ancient and modern who, although attracted by its sensuous qualities, regarded it rather slightingly as a cancer on the body of Arab classicism. This appeal to the western ear, no doubt, helped enormously in its incorporation into European music.

The early Provençal epic poems were modeled on the zajal. So striking in form and content is the poetry of southern Europe to the zajal that it cannot be regarded as a coincidence. The first known European poet of courtly love, Prince William, Duke of Aquitaine, is said to have spoken Arabic and is believed to have been familiar with both themuwashshahat and zajal. His poetry is a direct imitation of the Arabic rather than an independent invention. The rhythm of his early verses is very similar to songs still being recited in North Africa.

There is little question that the songs and music of the muwashshahatand zajal also gave rise to the famous troubadours. Besides their name, which is derived from the Arabic a raba (to play music) and dar(house), they carried on their entertainment in the same fashion as the Arab bards of Andalusia.

In Moorish Spain, the land was filled with poets and musicians. Music, song and dance were to found in the streets and in homes. Musicians and singers entertained in public or were often hired to perform in the homes of both wealthy and poor. It was said of them that they a rabu al-dar (entertained the home), hence, troubadour. Lovers would hire these musicians to serenade the object of their love. Today, the guitars have replaced the lutes, but the Don Juans continue with the wooing in the same fashion as the Moors.

T. Burckhardt in Moorish Culture in Spain writes that the origin of the minnesongs (poems of courtly love), which began in Provence and swept through the German-speaking countries lay in Moorish Andalusia. Others authors maintain that the German lieden, balades, rondo and la rodet, which are translations of the Arabic word nubah(turn or round), were all taken from the muwashshah and zajal of Moorish Spain.

Researchers have found unquestionable connections between the graduates of Ziryab’s academies in Cordova and other Spanish cities with the European music of the subsequent centuries. There is concrete evidence that from these houses of learning Arab music and song spread to the neighbouring lands and greatly influenced European popular merrymaking.

The Spanish Arabs’ setting of popular poetry to music and sung in themuwashshah and zajal styles was made when the Moors were the catalysts for world advancement. Hence, their legacy in European cultures, including music, had a solid foundation. One must remember that for centuries, in Europe, it was the Arabs of Spain alone who held, bright and shining, the torch of learning and civilization. It is not strange then that this glow aided in lighting the path for Europe’s progress in the field of music and song – much of this by the way of themuwashshah and zajal poetry.

REFERENCES

Al-Faruqi, L.I., ” muwashshah : A Vocal Form in Islamic Culture”Ethnomusicology, Vol. X1X, Number 1, Jan. 1975, The Society for Ethnomusicology, Inc., Ann Arbor, pp 1 to 29.

Burckhardt, T.’, Moorish Culture in Spain, Translated by A. Jaffa, George Allen,& Unwin Ltd., London, 1972.

Chejne, A.G., Muslim Spain – Its History and Culture, The University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1974.

Hole, E.C., Andalus: Spain Under the Muslims, Robert Hale Ltd., London, 1958.

Imamuddin, S. M., Muslim Spain, E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1981.

Lewis, B., Islam and the Arab World, Faith, People,. Culture, McClelland and Stewart Ltd., Toronto, 1976.

Livermore, A., A Short History of Spanish Music, Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd., London, 1972.

Lowe, A., The South of Spain, Collins, London, 1973.

Nykl, A.R., Hispano-Arabic Poetry and Its Relations With the Old Provençal Troubadours, J.H. Furst Co., Baltimore, 1970

Al-Makkari, Ahmed Ibn Mohammed, The History of the Mohammedan Dynasties in Spain, Johnson Reprint Co., London & New York, 1964.

O’Callaghan, J .F., A History of Medieval Spain, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, 1975.

Payne, S.G., A History of Spain and Portugal, The University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1973.

Read, J., The Moors in Spain and Portugal, Faber and Faber, London, 1974.

Russell, P .E., Spain – A Companion to Spanish Studies, Methuen & Co. Ltd., London, 1973.

Seman, K .1., Islam and the Medieval West, State University of New York Press, Albany, 1980.

Wasserstein, D., The Rise and Fall of Party Kings, Politics and Society in Islamic Spain, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1985.

Watt, W.M., A History of Islamic Spain, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 1965.

Dictionaries

The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Vol. 13&l7, Edited by Stanley Sadie, Macmillian Publishers Ltd., London, l980.

The New Oxford History of Music, Ancient and Oriental Music, Vol. 1, Edited by Egon Wellesz, Oxford University Press, London, 1957.