Chapter II

On Historical Origins of Arabic Script and Historical Development of Kufi Calligraphy

When I first decided to write about my Kufi calligraphy and Kufic scripture in general, I thought this was a new opportunity to convey all my ideas more clearly within the illuminating light of Kufic script.

Naturally, I’ve already read many well-written books on the paleography and epigraphy of Arabic script by famous Orientalists. Of course, I’ve also read many books, even some manuscripts, by Arab, Persian, or Turkish writers. However, I don’t believe it’s necessary to repeat all the knowledge I’ve gathered from those books—all the known and unknown aspects of the subject. Instead, I’ll offer my interpretations whenever it seems proper to me. Nevertheless, this essay will naturally include a bibliography for the more interested reader who wishes to learn more.

Let us recall some historical knowledge about the Arab people and the Qur’an: According to the Muslim religion, the Qur’an is the word of Allah revealed by the archangel Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad. Traditionally, Arab people are divided into two groups: Adnani (northern Arabs considered Arab i-mustaribe—that is, “Arabized Arabs” descended from Ishmael)—and Qahtani (southern Arabs, like the Yemenis).This is why northern Arabs are called ‘The sons of Ishmael’ by the Jews. According to the Old Testamen, Abraham and Hagar’s son Ishmael had ten children. The names of Ishmael’s first and second sons given by the Old Testament seemed interestingly historical to me referring nabatian and Kedar kingdoms. Nebaioth, the firstborn of Ishmael, and Kedar. *1. The name Nebaioth seems related to the Nabataean people, and according to paleographic and epigraphic investigations by Orientalists, the most widely held guess among them is that Arabic script originated from the Nabataean script.

Indeed, the history of Kufi script again clearly shows us the dubious nature of historical knowledge. The origin of Arabic script is not clear at all. There are only different predictions by some Orientalists based on various inscribed relics.

I think the aforementioned short remarks about my epistemological reasoning are sufficient to demonstrate my standpoint regarding the historical, theological, mystical, semantic, and artistic aspects of Kufic scripture. As it is said in Ecclesiastes II-8: “All things are hard: man cannot explain them by word. The eye is not filled with seeing, neither is the ear filled with hearing.”

Thus, the origins of the Arabic script have been a subject of scholarly debate for centuries. There are two main theories about its origins: the Nabataean Theory and the Musnad Theory.

The modern and most widely accepted theory is that the Arabic alphabet evolved from the Nabataean script, which itself was derived from the Aramaic alphabet. This evolution followed this path:

Phoenician alphabet → Aramaic alphabet → Nabataean Aramaic → Nabataean Arabic → Paleo-Arabic → Classical Arabic → Modern Standard Arabic

| Phoenician | Aramaic | Nabataean | Arabic | Syriac | Latin | |

| Image | Text | |||||

| 𐤀 | 𐡀 | ﺍ | ܐ | A | ||

| 𐤁 | 𐡁 | ٮ | ܒ | B | ||

| 𐤂 | 𐡂 | حـ | ܓ | C | ||

| 𐤃 | 𐡃 | د | ܕ | D | ||

| 𐤄 | 𐡄 | ه | ܗ | E | ||

| 𐤅 | 𐡅 | ﻭ | ܘ | F | ||

| 𐤆 | 𐡆 | ر | ܙ | Z | ||

| 𐤇 | 𐡇 | ح | ܚ | H | ||

| 𐤈 | 𐡈 | ط | ܛ | — | ||

| 𐤉 | 𐡉 | ى | ܝ | I | ||

| 𐤊 | 𐡊 | كـ | ܟ | K | ||

| 𐤋 | 𐡋 | لـ | ܠ | L | ||

| 𐤌 | 𐡌 | مـ | ܡ | M | ||

| 𐤍 | 𐡍 | ں | ܢ | N | ||

| 𐤎 | 𐡎 | — | ܣ | — | ||

| 𐤏 | 𐡏 | عـ | ܥ | O | ||

| 𐤐 | 𐡐 | ڡـ | ܦ | P | ||

| 𐤑 | 𐡑 | ص | ܨ | — | ||

| 𐤒 | 𐡒 | ٯ | ܩ | Q | ||

| 𐤓 | 𐡓 | ﺭ | ܪ | R | ||

| 𐤔 | 𐡔 | سـ | ܫ | S | ||

| 𐤕 | 𐡕 | ٮ | ܬ | T | ||

* 2.

The Nabataean script was used by the Nabataean Kingdom, centered in Petra (in modern-day Jordan) from around the 3rd century BCE. The Nabataeans were predominantly Arab Semitic tribes living in the area, controlling trade routes from the eastern Mediterranean shores to Hijaz (Saudi Arabia) and Yemen. A transitional phase between the Nabataean Aramaic script and a subsequent, recognizably Arabic script, is known as Nabataean Arabic. The pre-Islamic phase of the script as it existed in the fifth and sixth centuries CE, once it had become recognizably similar to the script as it came to be known in the Islamic era, is known as Paleo-Arabic.

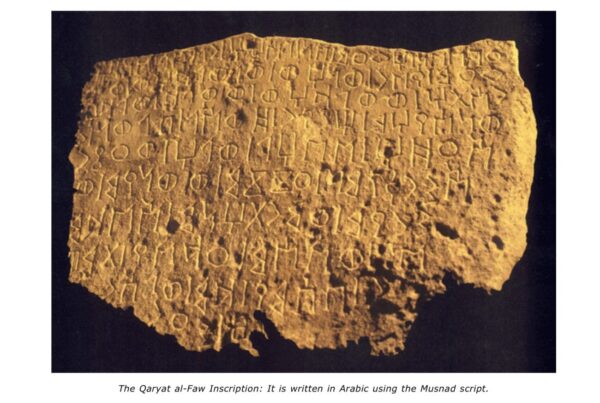

An alternative Musnad Theory suggests that the Arabic script can be traced back to Ancient North Arabian scripts, which are derived from the ancient South Arabian script (Arabic: khaṭṭ al-musnad).

*4,.

This hypothesis has been discussed by Arabic scholars Ibn Jinni and Ibn Khaldun. Some scholars, like Ahmed Sharaf Al-Din, have argued that the relationship between the Arabic alphabet and the Nabataeans is only due to the influence of the latter after its emergence (from Ancient South Arabian script). Arabic has a one-to-one correspondence with ancient South Arabian script except for one letter. German historian Max Muller (1823-1900) thought the Phoenician script was adapted from Musnad during the 9th century BCE when the Minaean Kingdom of Yemen controlled areas of the Eastern Mediterranean shores. Syrian scholar Shakīb ´Arslan shares this view.*5

To explore the history of the Kufic script is not merely to trace the formal evolution of a writing style. It also raises critical questions of historiography and epistemology. The origins of writing, its transformations, the contexts of its use, and the aesthetic choices it entails are shaped not only by material evidence but also by historical assumptions, intellectual frameworks, and interpretive narratives.

That is, historical origins of the Kufic script are not limited to the linear evolution of the Arabic script; they also reflect a broader cultural, political, and theological transformation. The development of Kufic writing corresponds with a rapidly evolving epistemological and aesthetic quest in the wake of Islam’s emergence. As a script, Kufic embodies the early Muslim community’s dual concern: preserving the Qur’anic revelation with precision and imparting to it a form of solemnity and visual dignity.

Because I do not wish to write a large book volume about the paleography of Arabic script, like many Orientalists have done before me, I will only mention here some good sources—which are easily reachable on the internet—about the history of “Arabic people, Arabic inscriptions, Arabic script, and Kufic scripture, etc.”*6.

One can find many examples from the Nabataean script and other Arabic inscriptions discovered by archaeologists on internet sites. There are some websites on the internet that show all the Arabic inscriptions and scripts, including new archaeological discoveries, such as:

- Digital archive for the study of pre-Islamic Arabian inscriptions: https://dasi.cnr.it/

- History of the Arabic alphabet – Wikipedia

- https://corpuscoranicum.de/en

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Arabic_inscriptions

- https://www.islamic-awareness.org/history/islam/inscriptions

Rather than conveying all the historical information I’ve gathered from the books of Orientalists and Muslim scholars, I wish to interpret certain aspects of Kufic scripture as they relate to various differing perspectives, whenever it seems imperative to do so. This is precisely why I have already articulated my epistemological standpoint concerning the myriad viewpoints across different disciplines. For instance, we possess numerous historical relics of Arabic scripts—inscriptions, papyri, manuscripts written on parchment, and later, coins minted by Umayyads, as well as buildings like the Dome of the Rock, which is ornamented with Kufic calligraphy. It seems scholars can never fully agree on these matters: the origin of the Arabic people, Arabic language, Arabic script, and Kufic script all appear dubious to me due to the many divergent interpretations offered by historians. It seems so confusing to me that I suspect these paleographic and epigraphic studies, with their vast amounts of comparable data, could only be analyzed effectively by artificial intelligence. It’s not necessary here to reiterate all the perplexing details of paleographic investigations; nevertheless, I will provide a comprehensive bibliography for curious readers, and many useful websites contain all those specific details.

For now, I will recall what Wordsworth once said:

Enough of science and of art

Close up those barren leaves

Come forth and bring with you a hearth

That watches and receives.

- Kufic Script: The Incarnation of the Word

How, then, can we “watch and receive,” and truly comprehend the meaning of Kufi calligraphy? First of all, in pre-Islamic Arab societies, writing was a limited skill, primarily practiced within narrow circles. It was used mainly for commercial contracts, epitaphs, and occasionally for recording poetry. With the revelation of the Qur’an, however, writing underwent a qualitative transformation. Soon after the death of prophet, the imperative to preserve and disseminate the divine message necessitated the standardization and refinement of the script.

What is the importance of Kufic script, and what is its aesthetic value? First and foremost, there was no developed Arabic script during the Prophet’s era, whether its origins lay in Nabataean script, Lakhmid script, or Syriac influence. It was certainly a distant relative, perhaps the last descendant, of the Phoenician alphabet. That script was not a full alphabet but an abjad. This means it primarily indicates only the consonants of words. Moreover, even with 28 consonants, only 18 had distinct sign symbols. The remaining consonants would later be indicated by the addition of different points, but even during the time of Uthman, these points were absent. The remaining letters were written with the same signs, later in Umayyad Era these same looking letters differentiated by the addition of dots. So the script evolved sufficiently to write Arabic only during the era of Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan.*7

Yet Kufic script stands as the oldest and most significant style of Arabic script, indeed the most formative visual art of Islam. So profound was its influence that Islamic civilization itself became a civilization of scripture, a Kufic calligraphy civilization. In Christianity, Jesus is regarded as an incarnation of God, sometimes phrased as the Son of God or the Word of God. Similarly, Kufic calligraphy can be seen as the incarnation of the Word of God. This is because the Qur’an itself is considered the Word of God, intermittently revealed by Gabriel, and thus, Qur’anic verses could be regarded as excerpts from the heavenly guarded book of destiny, the Levh-i Mahfuz.

From its inception, it was not merely an ordinary script but a holy scripture of the mushaf (book), the sacred text of the Qur’an. Kufic calligraphy itself emerged and developed specifically because of the Qur’an. Otherwise, it remained an unpractical and undeveloped script, perhaps rarely employed by a few merchants. Arabic sources indicate that only about 30 individuals in Mecca possessed writing skills, and some of them were indeed employed by the Prophet as scribes of revelation. In fact, Arabs had a predominantly oral culture before the Qur’an and did not favor writing extensively; their literature consisted primarily of poetry, which was also preferred to be memorized and recited by heart. Consequently, no Arabic script developed sufficiently for written books existed at that time. Even the word “Qur’an” itself means “recited aloud verses”; it refers not to a physical book but to a recitation, not yet compiled during the Prophet’s time, and primarily conveyed through memorization. I will not delve into the detailed discussions about how the Qur’an was eventually compiled into a suhuf (collected surahs and verses between two covers, resembling a book) during the time of the first Caliph Abu Bakr.

It was during the reign of Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan that some points and vowel signs were added to these letters to facilitate easier and more accurate reading. Therefore, if only a rudimentary Arabic script was rarely used during the Prophet’s time, and a fully developed Arabic script did not exist then, it implies that both the Arabic script and Arabic language grammar owe their development significantly to the imperative of writing the Qur’an. Subsequently, this script would come to be known as Kufic script.

- Early Kufic Characteristics and the “Misnomer” Debate

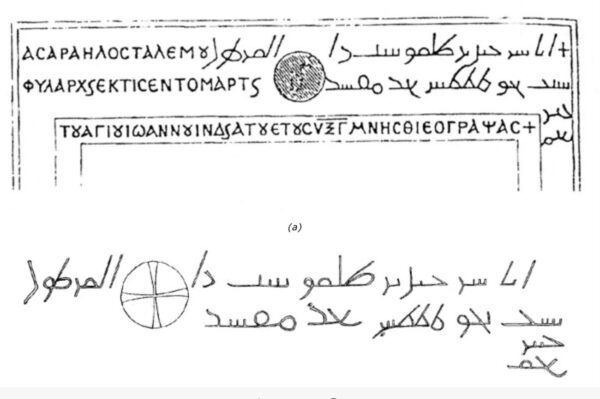

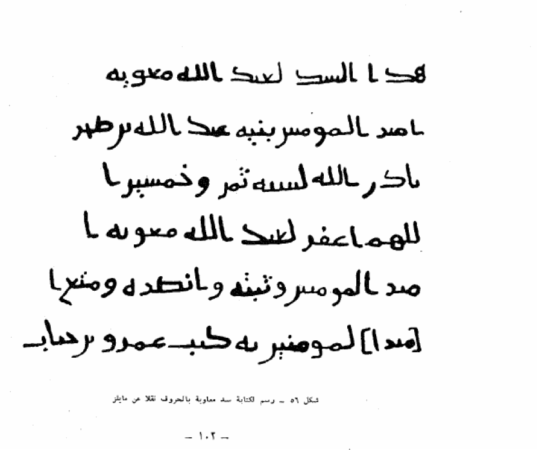

Here is an example of an inscription from the time of Muawiyah that already demonstrates the angular and rectilinear character of the Kufi style. This is a natural consequence, as it is inherently easier to engrave straight lines on the hard surface of a rock.

Location: Near Ṭa’if in the Ḥijaz, Saudi Arabia. (Excerpted From islamic-awareness.org)

The name “Kufic” is derived from the city of Kūfa in Iraq—an important intellectual and political center during the early Islamic period. In fact, it is a misnomer because the term denotes more than a mere geographic origin; it signifies a particular aesthetic discipline and a rich scriptural tradition. Compared with the more cursive and rounded Ḥijāzī script used in the Arabian Peninsula, Kufic is distinguished by its angularity, symmetry, and a structurally rigorous order.

The inscription shown above could indeed be called an example of Kufic script due to its rectilinear and angular letters. However, these characteristics largely stem from the inherent difficulty of engraving certain letter shapes on a hard rock surface. This method offers the simplest way to engrave an inscription on rock, as carving cursive letters would be considerably more challenging.

If the sole defining characteristic of Kufic calligraphy is its rectilinear and angular nature, then this inscription certainly appears to be an example of a primitive Kufic script. Kufi was the general designation for scripts featuring rectilinear and angular letter shapes, and there were no strict rules of proportion or any specific shaping style for individual letters until the emergence of other calligraphic styles. Later calligraphic letters somewhat resemble contemporary typography, where every letter is written in precisely the same shape and proportion each time it recurs. In contrast, there is no such rigid rule for Kufi calligraphy, apart from its generally more angular and rectilinear appearance when compared to other cursive handwritings. Kufi served as the general name for calligraphy for centuries until the advent of other calligraphic styles around the 11th century. In essence, the term “Kufic calligraphy” is also a misnomer, attributed to numerous distinct Kufi styles and to the city of Kūfa itself. I do not wish to reiterate all that has been written about Arabic paleography and calligraphy; while such details might be important from the perspective of specialized scholarly investigations or debates, it seems unproductive to repeat all those dubious and confusing statements here. Scholars have assigned names to every different handwriting style by comparing extant manuscripts, referring to them as Mekki, Medeni, Hicazi, Basri, Kufi, etc. Supposedly, Kufi developed in Kufa city, hence the misnomer. Certainly, there is a majestic geometrical style commonly referred to as Kufi, as seen in the parchment manuscripts of the Qur’an, which conveys the sacredness of the word of Allah within the awesome beauty of its mystical Kufic style. But how can we definitively know that it developed particularly in Kufa City? And what exactly does this misnomer “Kufi” signify anyway? History reveals many different styles of Kufi; which one is specifically meant by the name “Kufi”?

Sheila S. Blair suggests that “the name Kufic was introduced to Western scholarship by Jacob George Christian Adler (1756–1834).”

A more interested reader can delve into what ancient Islamic sources say about Kufi calligraphy by reading the first chapter of the book “İslam Kültür Mirasında Hat Sanatı” (The Art of Calligraphy in Islamic Cultural Heritage), written by Nihad M. Çetin and published by IRCICA. *7.

Some scholars propose Arabic script originated from Musnad/Himyarī, others from Nabataean script, while still others discuss Syriac influence. All these debates involve a certain amount of guesswork. The same applies to the misnomer “Kufic.” Scholars categorize some styles based on their supposed geographical centers, naming them Mekki, Medeni, Hicazi, Kufi, etc. In reality, these names merely designate different handwriting styles of the scripts. While “naming” should aid cognition and understanding, it does not necessarily imply a concrete entity and can sometimes lead to confusion. I believe all these perplexing paleographic, epigraphic, and calligraphic discussions would be best transferred to an AI agent for analysis. Nevertheless, this art form continues to be referred to by the name Kufi calligraphy, even though it does not adhere to any strict rules of calligraphic measures when compared to the letters of the so-called “Aklam-ı Sitte” / “Six Kinds of Pen,” which developed later in the 11th century.

Here is the description provided about the first manuscripts in the Fihrist (Index of Books) by the Baghdadi bibliographer al‐Nadim, written in 987:

“The first Arabic scripts were the Meccan and after that the Madinan, then the Basran, then the Kufan. As regards the Meccan and Madinan, there is in its [sic] alifs a bend to the right hand side and an elevation of the vertical strokes; and in its form, there is a slight inclination…” =

3.Evolution and Standardization of the Script

During the early Islamic period, the Arabic script remained in a relatively primitive state. It conspicuously lacked diacritical marks (dots) to distinguish between similar letters and contained no vowel markings. This deficiency made reading arduous, particularly for non-native Arabic speakers, as Islam rapidly expanded beyond the Arabian Peninsula. The third caliph, Uthman ibn Affan (r. 644-656 CE), commissioned the first official compilation of the Qur’an, thereby establishing a standard text. This monumental project necessitated significant improvements in the writing system to ensure the accurate preservation of the sacred text. Under the Umayyad Caliphate (661-750 CE), pivotal developments transpired:

- Introduction of Diacritical Marks: Abu al-Aswad al-Du’ali (d. 688 CE) is traditionally credited with introducing dots to differentiate between otherwise identical letters.

- Vowel Notation System: A system utilizing colored dots was devised to indicate short vowels, which are conventionally not written in Arabic script.

- Standardization: The script became progressively more standardized as its use expanded for administrative purposes throughout the burgeoning Islamic empire.

These innovations proved indispensable for preserving the correct recitation of the Qur’an and for facilitating the widespread adoption of Arabic literacy among non-Arab converts to Islam.

The mention of inclined letters in al-Nadim’s Fihrist renders the reference to this primitive corpus unambiguous. However, how prevalent were the denominations “Meccan” and “Madinan” during al-Nadim’s lifetime, and for how long had they been in existence by then? Were they intended to encompass all of the earliest Qur’anic scripts, or merely specific stylistic tendencies within them? Al-Nadim offers no further elaboration on the subject nor does he cite his sources.

The Qur’anic codices produced during the caliphate of ʿUthmān may not yet have been strictly termed “Kufic,” they indisputably represent a foundational stage in its development. These early codices notably lacked diacritical marks and vowel signs—a reality that, given the polysemic nature of Arabic, frequently led to interpretive ambiguities. This intrinsic challenge propelled the gradual elaboration of a more precise writing system.

The Umayyad period witnessed the seminal introduction of diacritical markings by Abū al-Aswad al-Duʾalī, subsequently followed by the contributions of al-Khalīl ibn Aḥmad, who further refined the dotting system. These innovations substantially enhanced the clarity and functionality of the Arabic script, thereby reinforcing the pivotal role of Kufic script in the preservation and transmission of the Qur’an.

4,Kufic’s Expansion and Artistic Maturation

By the 8th and 9th centuries, Kufic was no longer confined exclusively to Qur’anic manuscripts. It began to proliferate across diverse media—architecture, coinage, ceramics, textiles, and metalwork. This significant diversification signals that Kufic had evolved into both a functional script and a potent symbolic medium. It matured into an aesthetic form that could be visually apprehended, physically touched, and seamlessly integrated into spatial environments.

During the Abbasid period, the formal institutionalization of calligraphy as an art form played a decisive role in the full maturation of Kufic script. Major cultural centers such as Baghdad, Kūfa, and Baṣra saw the burgeoning of scriptoria and schools dedicated to its ongoing development. Consequently, various regional and functional styles of Kufic began to emerge, including Eastern Kufic (mashriqī), Western Kufic (maghribī), Square Kufic (murabbaʿ), and ornamental Kufic, among others. Each distinct variant reflects specific cultural and aesthetic evolutions of the script.

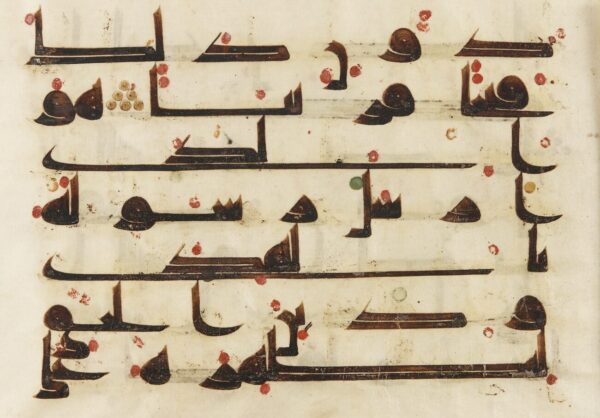

From a paleographic perspective, studying the transformation of Kufic script offers critical insights into the broader history of writing itself. Early Qur’anic manuscripts typically featured large letters and generous spacing between lines. Over time, the script became more compact, stylistically elaborate, and enriched with decorative elements. These progressive changes reflect not only technical innovations in writing but also profound shifts in aesthetic sensibilities, religious consciousness, and political symbolism within Islamic societies.

In summary, Kufic script emerged from within the nascent Arabic script tradition but rapidly transcended it, becoming a multifaceted cultural form that eloquently conveyed the sacred and aesthetic codes of Islamic civilization. Its paleographic evolution distinctly mirrors the broader transformation of Islamic societies—their core values, modes of expression, and distinct approaches to textuality. Thus, Kufic is not merely a relic of the distant past; it stands as one of the clearest indicators of how the written word has historically functioned as a profound bearer of faith, art, and identity.

5,Kufic as an Archetype and Its Diverse Styles

Kufic represents the oldest calligraphic form; it developed around the seventh century, and by the orders of Caliph Uthman ibn Affan, it was extensively and exclusively employed for copying the Qur’an until the eleventh century. The Kufic script is a style of Arabic script that gained early prominence as the preferred script for Qur’an transcription and architectural decoration, and it has since become a fundamental reference and an archetype for numerous other Arabic scripts.

Kufic is characterized by its angular, rectilinear letterforms and its pronounced horizontal orientation. According to Enis Timuçin Tan, a primary characteristic of the Kufic script “appears to be the transformation of the ancient cuneiform script into the Arabic letters.” Furthermore, it was marked by figural letters specifically shaped to be beautifully rendered on parchment, buildings, and decorative objects like lusterware and coins.

Kufic script is fundamentally composed of geometrical forms such as straight lines and angles, alongside clear verticals and horizontals. Initially, Kufic did not possess what is now known as differentiated consonants, meaning, for example, that the letters “t,” “b,” and “th” were not distinguished by diacritical marks and appeared identical. During the first few centuries of Islam, Arabic was written without any vowel marks or dots, unlike how the Arabic script appears today. This was because these auxiliary markers were not yet necessary; the early Muslims were native Arabic speakers and could thus read the Qur’an without such aids. However, this changed as Islam expanded, becoming a multinational and multiracial religion. The necessity for vowel markings and dots arose to denote different sounds and establish distinctions between similar-looking characters, and these additions remain integral to the Qur’an today. The Kufic script dots were sometimes rendered in red ink. It is believed that a scribe named Abdul Aswad was the first to introduce these markings .

The Qur’an was initially written in a plain, slanted, and uniform script, but once its content became formalized, a script signifying authority emerged. This coalesced into what is now known as Primary Kufic script. Kufic was widely prevalent in manuscripts from the 7th to the 10th centuries. Around the 8th century, with its austere and relatively low vertical profile and strong horizontal emphasis, it stood as the most important among several variants of Arabic scripts. Until approximately the 11th century, it served as the principal script used for copying the Qur’an. Professional copyists employed a specific form of Kufic for reproducing the earliest surviving copies of the Qur’an, which were written on parchment and date from the 8th to 10th centuries. In later Kufic Qur’ans of the ninth and early tenth century, “the sura headings were more often designed with the sura title as the main feature, often written in gold, with a palmette extending into the margin,” as noted by Marcus Fraser. One impressive example of an early Qur’an manuscript, known as the Blue Qur’an, features gold Kufic script on parchment dyed with indigo. It is commonly attributed to the early Fatimid or Abbasid court. The main text of this Qur’an is inscribed in gold ink, creating the striking effect of gold on blue when viewing the manuscript.

- Regional Variations and Styles of Kufic

There were no rigidly set rules governing the use of the Kufic script; its only consistent feature was the angular, linear shapes of its characters. Due to this lack of standardized methods, the scripts varied considerably across different regions, countries, and even among individual scribes, leading to diverse creative approaches. These ranged from very square and rigid forms to more flowery and decorative styles.

Several regional variations of Kufic script evolved over time:

- Maghribi (Moroccan or Western) Kufic: While still rigid, linear, and thick, Maghribi Kufic script features a significant amount of curves and loops, in contrast to the more rectilinear original Arabic Kufic script. Loops for characters such as the Waw and the Meem are notably pronounced and sometimes exaggerated.

- Kufi Mashriqi (Eastern Kufic): This is a thinner, more cursive, and decorative form of Kufic prevalent in eastern regions. The nib of the pen used for this style is finer, and it exhibits greater cursiveness, with some characters extending into long, sweeping strokes. Nevertheless, it remains within the angular vocabulary characteristic of Kufic script.

- Fatimi Kufi: Predominant in the North African region, particularly Egypt. Since this script is highly stylized and decorative, this form was primarily utilized in the ornamentation of buildings. Fatimi Kufi script can be observed with intricate decorations among the characters, suchulating the inclusion of the Endless Knot or vegetal motifs, both within the character itself and as a background design.

- Square Kufic (Murabba’ Kufi): Also known as geometric Kufic, this is a highly simplified rectangular style widely adopted for tiling. It is characterized by absolute straightness with no decorative accents or curves whatsoever. Due to this extreme rigidity, this type of script can be readily created using square tiles or bricks. It is particularly popular in Iran and Turkey, where in the latter, it was a favored decoration for buildings during the Ottoman Empire.

- Decorative Kufic: Primarily used for adorning daily items such as plates, bowls, vases, or ewers. Quite often, inscriptions executed in this script are barely legible due to the extensive ornamentation. A letter might virtually disappear within elaborate decorations that could involve transforming letters into vegetal forms like vines and leaves, or by being written very thinly with exaggerated vertical lines and curves.

- Ghaznavid and Khourasan Scripts: In Iran, in addition to Kufi Mashriqi script (also referred to as the Piramouz script), other forms include the Ghaznavid and Khourasan scripts. These scripts were mostly employed for monument decoration, coinage, and daily items. The Khourasan script is as thick as the Original Arabic Kufic script, but with a simple flair added to each character. The Ghaznavid Kufi features elongated vertical lines and rounded ends, often with surrounding decorations.

- Ornamental Use of Kufic Script

Ornamental Kufic emerged as a crucial element in Islamic art as early as the eighth century, serving for Qur’anic headings, numismatic inscriptions, and significant commemorative writings. The Kufic script is famously inscribed on textiles, coins, lusterware, buildings, and other artifacts. Coins, in particular, played a very important role in the development of Kufic script. Indeed, “the letter strokes on coins had become perfectly straight, with curves tending toward geometrical circularity by 86,” observes Alain George. As an example, Kufic is commonly seen on Seljuk coins and monuments and on early Ottoman coins. In Iran, entire buildings are sometimes covered with tiles spelling sacred names like those of God, Muhammad, and Ali in Square Kufic, a technique known as banna’i. There is also “Pseudo-Kufic” or “Kufesque,” terms that refer to imitations of the Kufic script made in a non-Arabic context during the Middle Ages or the Renaissance. The distinct artistic styling of Kufic eventually led to its decorative use in Europe, outside of an Arabic context, particularly on architecture.

The Enduring Legacy of Kufi Calligraphy

The history of Arabic script and Kufic calligraphy represents one of the most significant artistic and cultural developments in Islamic civilization. From its humble beginnings as a practical writing system to its elevation as a sublime art form, Arabic calligraphy has played a central role in shaping Islamic visual culture and identity. The development of Arabic script reflects the dynamic interplay of religious, political, cultural, and aesthetic factors throughout Islamic history. The early standardization efforts during the Umayyad and Abbasid periods laid the foundation for the flourishin of calligraphic arts. The contributions of master calligraphers like Ibn Muqla, Ibn al Bawwab, and Yaqut al-Musta’simi established systematic approaches to letter formation that continue to influence calligraphers today. Kufic calligraphy, with its distinctive angular character, holds a special place in this history as the first formalized style of Arabic script. Its use in early Quranic manuscripts and architectural decoration established a visual language that became immediately recognizable as Islamic. The evolution of Kufic into various regional styles demonstrates the adaptability and creative potential of this script. The political dimension of Arabic calligraphy cannot be overlooked. Throughout Islamic history, rulers and elites patronized calligraphers and used calligraphic inscriptions to assert their legitimacy and piety. The mutual relationship between political power andNcalligraphic development shaped the evolution of styles and techniques. The versatility of Arabic calligraphy is evident in its application across various media— from manuscripts to monumental architecture, from textiles to metalwork, from coins to ceramics. This adaptability allowed calligraphy to permeate all aspects of Islamic material culture, creating a unified visual language across diverse regions and periods. The significance of Arabic calligraphy extends far beyond its aesthetic appeal. As a sacred art connected to divine revelation, a cultural symbol that unites diverse communities, an aesthetic tradition of remarkable sophistication, an intellectual discipline that integrates various fields of knowledge, and a social practice embedded incomplex networks of patronage and power, calligraphy has played a central role in shaping Islamic civilization. In the contemporary world, Arabic calligraphy continues to evolve and adapt to new contexts while maintaining its connection to tradition. Modern calligraphers and artists draw inspiration from historical styles while experimenting with new materials, techniques, and compositions. Educational initiatives aim to preserve and transmit calligraphic knowledge to future generations. The enduring legacy of Arabic script and Kufic calligraphy can be seen in its continued vitality and relevance. As one source eloquently states, “Its historical roots, spiritual significance, and aesthetic beauty make it an integral part of Islamic heritage; whether engraved in the walls of a mosque or carefully inscribed upon the pages of a manuscript, Islamic calligraphy invites us to pause, reflect, and appreciate the beauty of words written in the name of Allah” In a world increasingly dominated by digital communication and mass-produced imagery, the handcrafted beauty and spiritual depth of Arabic calligraphy offer a powerful reminder of the potential for human creativity to express and embody sacred values. The tradition of Arabic calligraphy thus stands as one of the most significant and distinctive contributions of Islamic civilization to world culture, a living tradition that continues to evolve while maintaining its essential connection to its spiritual and cultural roots.

Contemporary Significance Cultural Heritage and Identity

In the contemporary world, Arabic calligraphy continues to serve as an important marker of cultural heritage and identity for Muslims. As traditional arts face challenges from globalization and technological change, calligraphy has taken on new significance as a link to Islamic cultural roots. Recognition of this importance can be seen in recent initiatives like Saudi Arabia extending the Year of Arabic Calligraphy into 2021 and UNESCO registering the art form on its Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage. These efforts reflect a growing awareness of the need to preserve and promote calligraphic traditions for future generations.

Timeline of Arabic Script and Kufic Calligraphy

Here is a timeline of the historical developments of the Arabic script and Kufic calligraphy, enriched with additional information, relics, and milestones:

| Time Period | Development | Key Relics and Examples |

| 4th Century CE | Early Arabic script emerges, influenced by the Nabataean script, which itself derives from the Aramaic script. | Nabataean inscriptions in Petra (modern-day Jordan) show the transition from Aramaic to early Arabic forms. |

| 6th Century CE | Pre-Islamic Arabic script develops further, used for inscriptions | The Namara Inscription (328 CE), an early Arabic inscription, is a key example of pre-Islamic script. |

| 7th Century CE | Kufic calligraphy becomes the primary script for transcribing the Quran. | Early Quranic manuscripts in Kufic script, such as fragments found in the Great Mosque of Sana’a, Yemen. |

| 7th Century CE (Later) | Abu al-Aswad al-Du’ali introduces diacritical marks to the Arabic script to ensure accurate Quranic recitation. | Early Quranic manuscripts with diacritical marks, attributed to Abu al-Aswad’s system. |

| 8th Century CE | Kufic calligraphy becomes widely used across the Islamic empire for Quranic manuscripts and architectural inscriptions. | The Samarkand Quran (8th century), one of the oldest surviving Quranic manuscripts in Kufic script. |

| 9th Century CE | Decorative Kufic styles emerge, incorporating geometric and floral motifs. The Blue Quran is produced, showcasing the luxurious use of Kufic script. | The Blue Quran (9th century), written in gold Kufic script on indigo-dyed parchment, believed to have been created in North Africa. |

| 10th Century CE | Ibn Muqla develops the principles of proportion in Arabic calligraphy, influencing the transition from Kufic to cursive scripts. | Manuscripts and inscriptions reflecting Ibn Muqla’s proportional system. |

| 11th Century CE | Ibn al-Bawwab refines Kufic and other scripts, elevating the artistic quality of Quranic manuscripts. | Quranic manuscripts attributed to Ibn al-Bawwab, showcasing his mastery of Kufic and cursive scripts. |

| 13th Century CE | Yaqut al-Musta’simi perfects the use of the reed pen and introduces innovations in script design, marking the culmination of classical Kufic calligraphy. | Manuscripts and inscriptions by Yaqut al-Musta’simi, demonstrating his innovations in Kufic and other scripts. |

| Seljuk Period (11th–13th Century CE) | Square Kufic (Ma’qili/murabba/bennai) style develops, used extensively in architectural decorations. | Architectural inscriptions in Square Kufic, such as those on Seljuk mosques and madrasas. |

| Mamluk Period (13th–16th Century CE) | Memluki Kufic style emerges, characterized by intricate and ornate designs. | Mamluk-era Quranic manuscripts and architectural inscriptions in Memluki Kufic. |

| Ottoman Period (14th–20th Century CE) | Square Kufic continues to be used in Ottoman architecture, blending with other decorative elements. | Ottoman mosques in Istanbul, such as the Süleymaniye Mosque, featuring Square Kufic inscriptions. |

| Modern Era (20th–21st Century) | Kufic calligraphy inspires contemporary art, graphic design, and architecture. | Modern artworks, public installations, and digital designs incorporating Kufic-inspired elements. |