Bismillah. alimet nefsün mâ kaddemet ve ahheret…

Gödel’s ontological proof as inspired by St Augustine & St Anselm…

Credo ut intelligam is Latin for “I believe so that I may understand” and is a maxim of Anselm of Canterbury, which is based on a saying of Augustine of Hippo (crede, ut intelligas, “believe so that you may understand”) to relate faith and reason. It is often accompanied by its corollary, intellego ut credam (“I think so that I may believe”), and by Anselm’s other famous phrase fides quaerens intellectum (“faith seeking understanding”).

et cognoscetis veritatem et veritas liberabit vos.

Ve Hakîkat râ hâhîd şinaht ve Hakîkat şümâ râ âzâd hâhed kerd:

Felix, qui potuit rerum cognoscere causas

VE HAKÎKATI BILECEKSINIZ VE HAKIKAT SIZI HÜR KILACAK

Neque enim quaero intelligere ut credam, sed credo ut intelligam. Nam et hoc credo, quia, nisi credidero, non intelligam. ” (“Nor do I seek to understand that I may believe, but I believe that I may understand. For this, too, I believe, that, unless I first believe, I shall not understand.”) St. Anselm

çünin Mevlânâ fermâyed ki:

“z’an taalluk kerd bâ cism-î ilâh

tâ ki gerded cümle âlem râ penâh”

Holy LogicComputer Scientists ‘Prove’ God Exists

By David Knight

picture-alliance/ Imagno/ Wiener Stadt- und Landesbibliothek

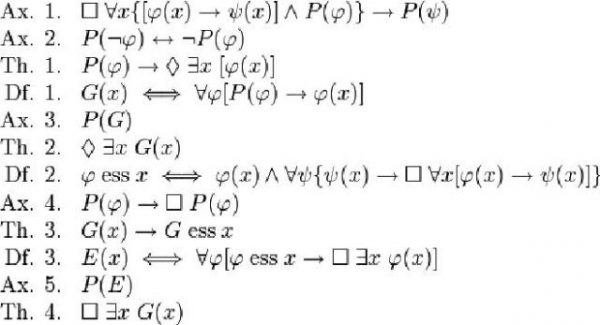

Austrian mathematician Kurt Gödel kept his proof of God’s existence a secret for decades. Now two scientists say they have proven it mathematically using a computer. Two scientists have formalized a theorem regarding the existence of God penned by mathematician Kurt Gödel. But the God angle is somewhat of a red herring — the real step forward is the example it sets of how computers can make scientific progress simpler. As headlines go, it’s certainly an eye-catching one. “Scientists Prove Existence of God,” German daily Die Welt wrote last week. But unsurprisingly, there is a rather significant caveat to that claim. In fact, what the researchers in question say they have actually proven is a theorem put forward by renowned Austrian mathematician Kurt Gödel — and the real news isn’t about a Supreme Being, but rather what can now be achieved in scientific fields using superior technology. When Gödel died in 1978, he left behind a tantalizing theory based on principles of modal logic — that a higher being must exist. The details of the mathematics involved in Gödel’s ontological proof are complicated, but in essence the Austrian was arguing that, by definition, God is that for which no greater can be conceived. And while God exists in the understanding of the concept, we could conceive of him as greater if he existed in reality. Therefore, he must exist. Even at the time, the argument was not exactly a new one. For centuries, many have tried to use this kind of abstract reasoning to prove the possibility or necessity of the existence of God. But the mathematical model composed by Gödel proposed a proof of the idea. Its theorems and axioms — assumptions which cannot be proven — can be expressed as mathematical equations. And that means they can be proven. Proving God’s Existence with a MacBook That is where Christoph Benzmüller of Berlin’s Free University and his colleague, Bruno Woltzenlogel Paleo of the Technical University in Vienna, come in. Using an ordinary MacBook computer, they have shown that Gödel’s proof was correct — at least on a mathematical level — by way of higher modal logic. Their initial submission on the arXiv.org research article server is called “Formalization, Mechanization and Automation of Gödel’s Proof of God’s Existence.” The fact that formalizing such complicated theorems can be left to computers opens up all kinds of possibilities, Benzmüller told SPIEGEL ONLINE. “It’s totally amazing that from this argument led by Gödel, all this stuff can be proven automatically in a few seconds or even less on a standard notebook,” he said. The name Gödel may not mean much to some, but among scientists he enjoys a reputation similar to the likes of Albert Einstein — who was a close friend. Born in 1906 in what was then Austria-Hungary and is now the Czech city of Brno, Gödel later studied in Vienna before moving to the United States after World War II broke out to work at Princeton, where Einstein was also based. The first version of this ontological proof is from notes dated around 1941, but it was not until the early 1970s, when Gödel feared that he might die, that it first became public. Now Benzmüller hopes that using such a headline-friendly example can help draw attention to the method. “I didn’t know it would create such a huge public interest but (Gödel’s ontological proof) was definitely a better example than something inaccessible in mathematics or artificial intelligence,” the scientist added. “It’s a very small, crisp thing, because we are just dealing with six axioms in a little theorem. … There might be other things that use similar logic. Can we develop computer systems to check each single step and make sure they are now right?” ‘An Ambitious Expressive Logic’ The scientists, who have been working together since the beginning of the year, believe their work could have many practical applications in areas such as artificial intelligence and the verification of software and hardware. Benzmüller also pointed out that there are many scientists working on similar subject areas. He himself was inspired to tackle the topic by a book entitled “Types, Tableaus and Gödel’s God,” by Melvin Fitting. The use of computers to reduce the burden on mathematicians is not new, even if it is not welcomed by all in the field. American mathematician Doron Zeilberger has been listing the name Shalosh B. Ekhad on his scientific papers since the 1980s. According to the New York-based Simons Foundation, the name is actually a pseudonym for the computers he uses to help prove theorems in seconds that previously required page after page of mathematical reasoning. Zeilberger says he gave the computer a human-sounding name “to make a statement that computers should get credit where credit is due.” “human-centric bigotry” on the part of mathematicians, he says, has limited progress. Ultimately, the formalization of Gödel’s ontological proof is unlikely to win over many atheists, nor is it likely to comfort true believers, who might argue the idea of a higher power is one that defies logic by definition. For mathematicians looking for ways to break new ground, however, the news could represent an answer to their prayers.