.

.

.

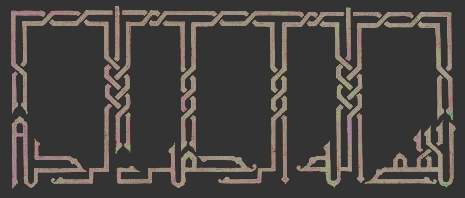

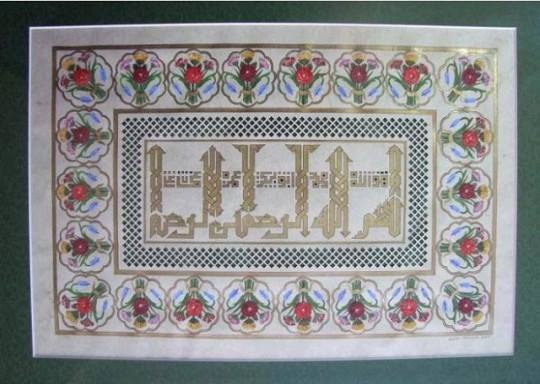

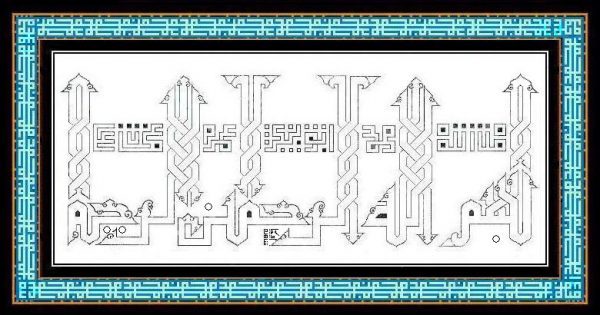

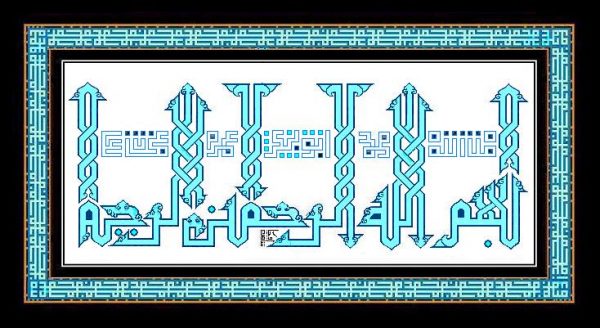

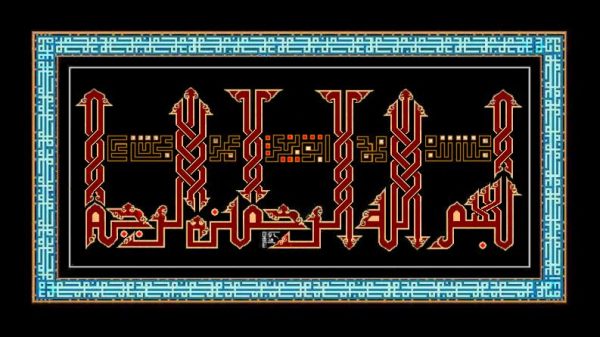

Bu Besmeleyi Aydın Bolak için yazmıştım. 1973 de

.Ben bazı eserlerimi kaybetsem de, insanların kadirşinaslığı sayesinde, bazen böyle hoş sürprizlerle tekrar ortaya çıkıyor. Nitekim, benim bu kufi besmelemi, Prof. Dr. İbrahim Yekeler 40 yıl muhafaza etmiş. Medyûn u şükrânım. Sonra İbrahim Beyin ablası da buna bir tezyinat yaptı.

besmelenin kenarındaki katı’ tezyinat: Edibe Yekeler

.

.

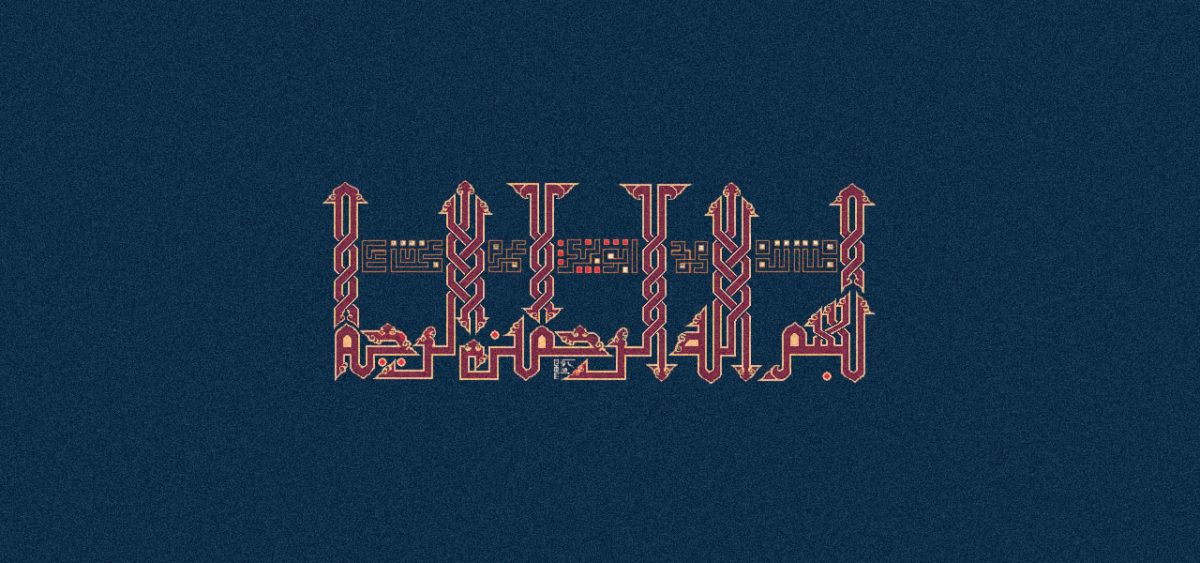

bu da anlatıldığı üzre o ilk karşılaşmamızda kaya bilgegil’e okuduğum gazel