Kufi Calligraphy and my Philosophy of History

اِقْرَأْ بِاسْمِ رَبِّكَ الَّذٖي خَلَقَۚ

,خَلَقَ الْاِنْسَانَ مِنْ عَلَقٍۚ

اِقْرَأْ وَ رَبُّكَ الْاَكْرَمُۙ

اَلَّذٖي عَلَّمَ بِالْقَلَمِۙ

عَلَّمَ الْاِنْسَانَ مَا لَمْ يَعْلَمْؕ

Recite: In the name of thy Lord who created

Created man of a blood-clot.

Recite: And thy Lord is the most Generous,

Who taught by the Pen

Taught Man, that he knew not

Qur’an/ The Blood-clot (1)

وَعَلَّمَ اٰدَمَ الْاَسْمَٓاءَ كُلَّهَا

And He taught Adam the names, all of them

Quran/ The Cow 31

Ma’nâ yı-kelâm şâhid i-mazmûn i-Hudâdır

Gönlüm sadefinden olur azrâ gibi peydâ

`The meaning of the word professes

the hidden existence of God in it: and this word, likewise a virgin pearl,

occurs in my heart which is the mother-of-pearl.”

Şeydâ Dîvânı, Tevhid Kasidesi

1. The Pen, the Preserved Tablet, and Divine Instruction.

سم الله الرحمن الرحيم الحمد لله الذي خلق القلم أولاً . و كتب الكتاب المكنون بذلك القلم في اللوح المحفوظ . و فيه كتب كل المقدّرات، من البداية إلى يوم القيامة. هو الله الخالق لكل أمرٍ و شأن. و الشكر لا يعد لمن خلق الإنسان و علّمه البيان . و هو علّم آدم الأسماء كلّها، و علّم بالقلم ، و علّم الإنسان ما لم يعلم . لأن الوحي الأوّل كان اقرأ باسم ربّك و قيل في تلك الآية هو الذي علم بالقلم .كما كان هذا القسم بالقلم في القرآن, ن و القلم و ما يسطرون …و في القرآن له آية تدل على ماهیت القرآن. بل هو قرآن مجيد في لوحٍ محفوظ

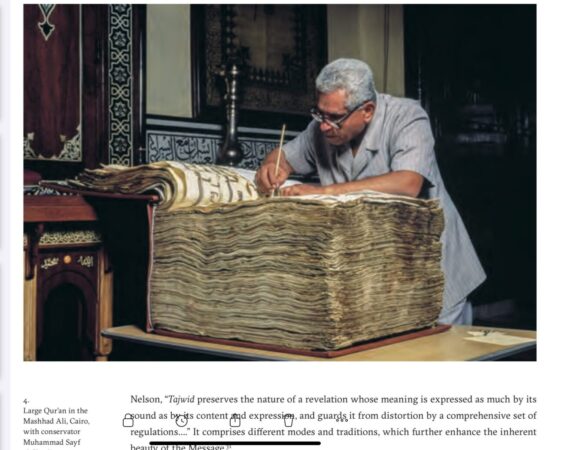

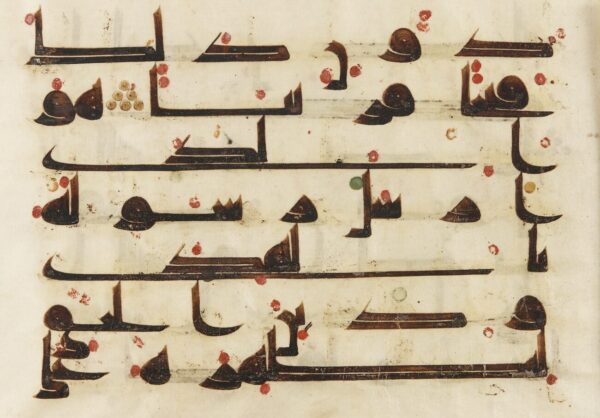

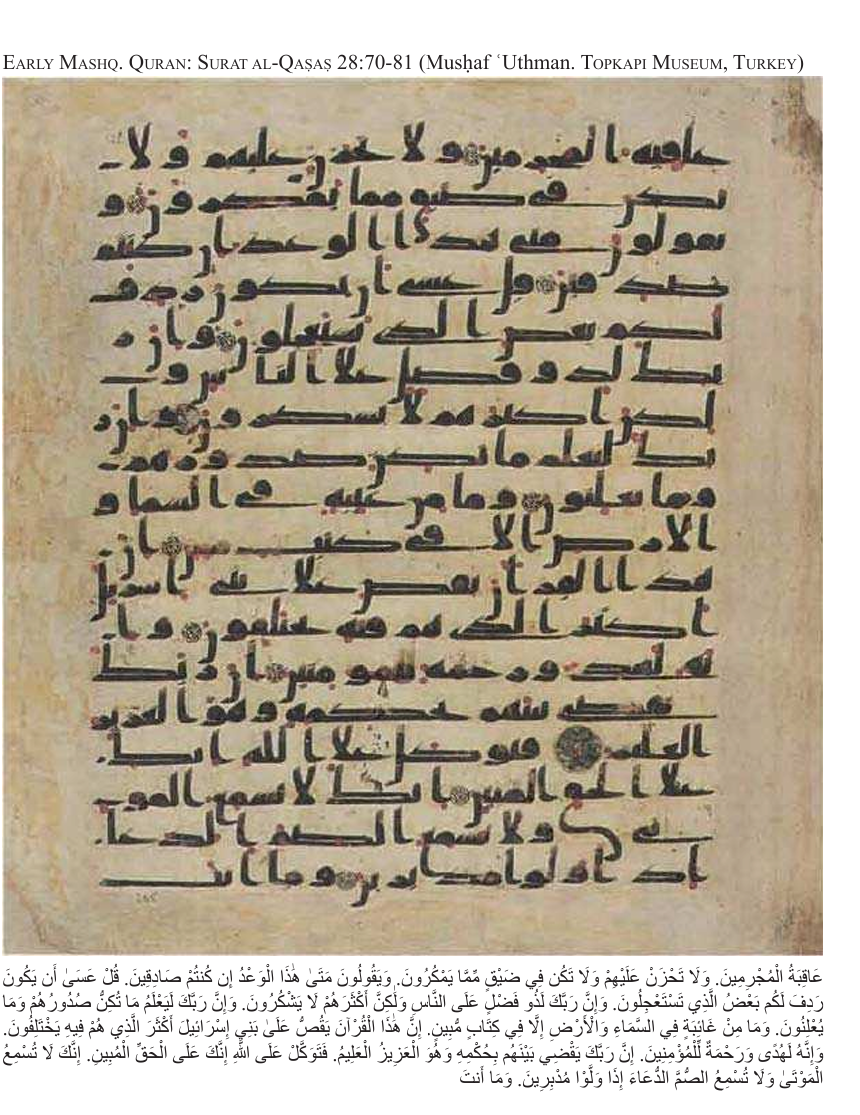

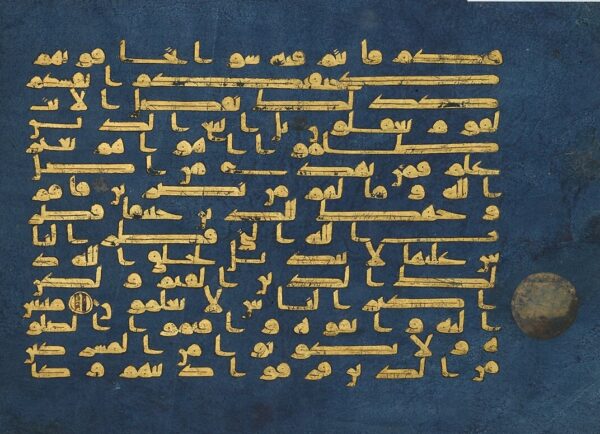

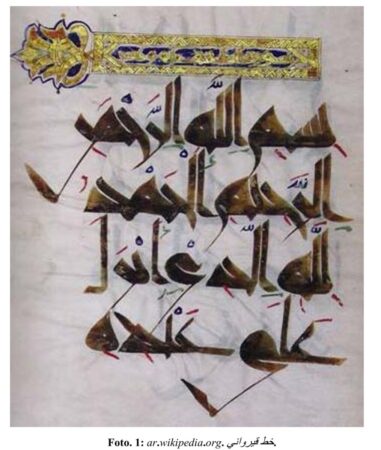

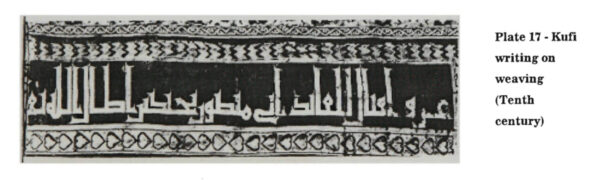

صلوا على محمّد هو كشف الدجى بنور الوحي و نوّر قلوب العارفين به . و بدأ الخط الكوفي في عصره ليكتب آيات القرآن ولقد كان القرآن مصدر الفكر والحضارة الإسلامية كلها. والقرآن كتب بالخط الكوفي لعدة قرون. ولهذا السبب أصبح الخط الكوفي أشهر في تمثيل الحضارة الإسلامية. كما كان الان . وهذا من فضل ربي

In the name of God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful

Praise be to God who created the Pen first and the hidden book was written with that pen on the Preserved Tablet. In it are written all the decrees, from the beginning until the Day of Resurrection. He is God, the Creator of every matter and phenomen. Countless Gratitude is to the One who created man and taught him speech. He taught Adam all the names, taught with the pen, and taught man what he did not know. Because the first revelation was “Read in the name of your Lord,” and it also was said in that verse: “He is the one who taught with the pen.” As this oath was in the pen in the Qur’an Nun, by the pen, and what the lines it writes…And in the Qur’an there is a verse that indicates that Qur’an is eternal. But rather it is glorious Qur’an in a preserved tablet.

Pray for Muhammad, he removes darkness with the light of revelation and enlightens the hearts of those who know him. In his era, the Kufic script began to write verses of the Qur’an, and the Qur’an was the source of all Islamic thought and civilization. The Qur’an was written in Kufi script for centuries. For this reason, the Kufic script became a representation of Islamic civilization. As it was now. This is from the grace of my Lord.

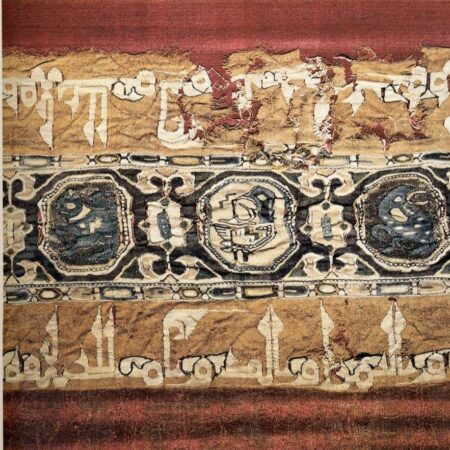

Thus, silent letters of the kufi script had become an embodiment of Kelamullah/ the Word of God; displaying all the resonant spectrum of enchanting melodic incantations of the recitations of Qur`an verses; thus it come to light and participate in every aspect of Islamic culture.

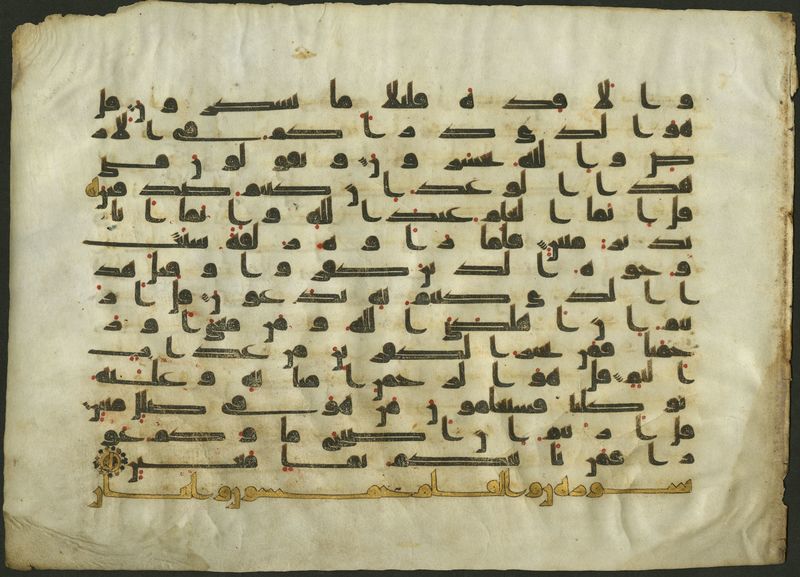

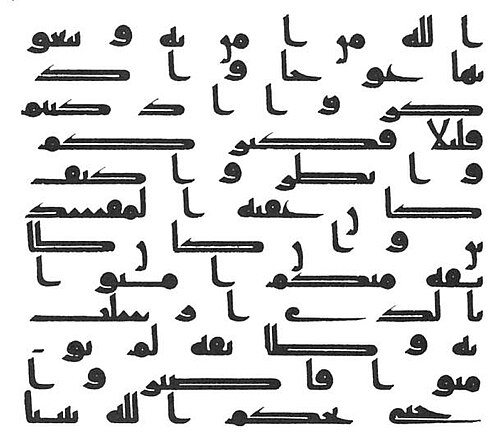

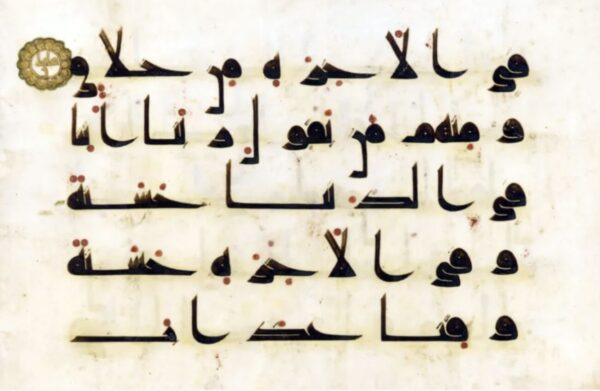

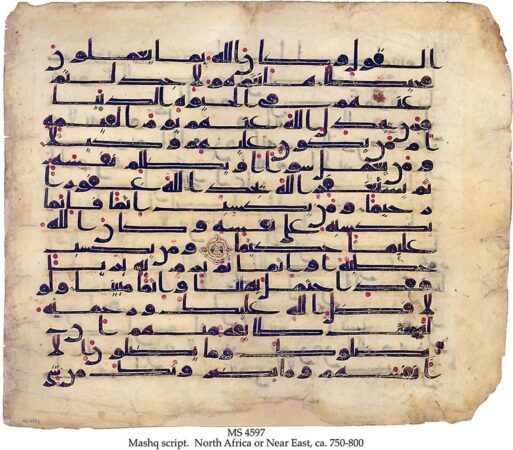

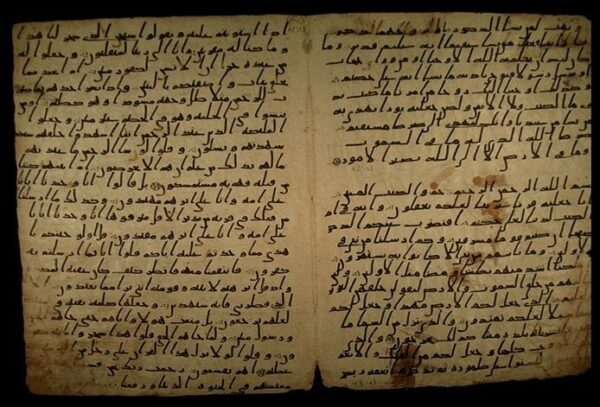

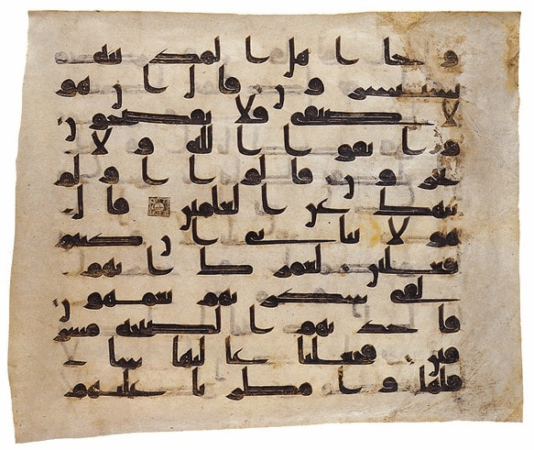

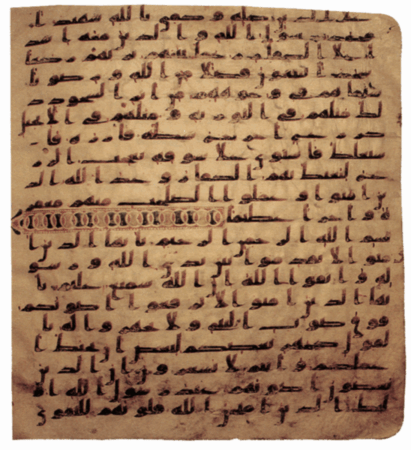

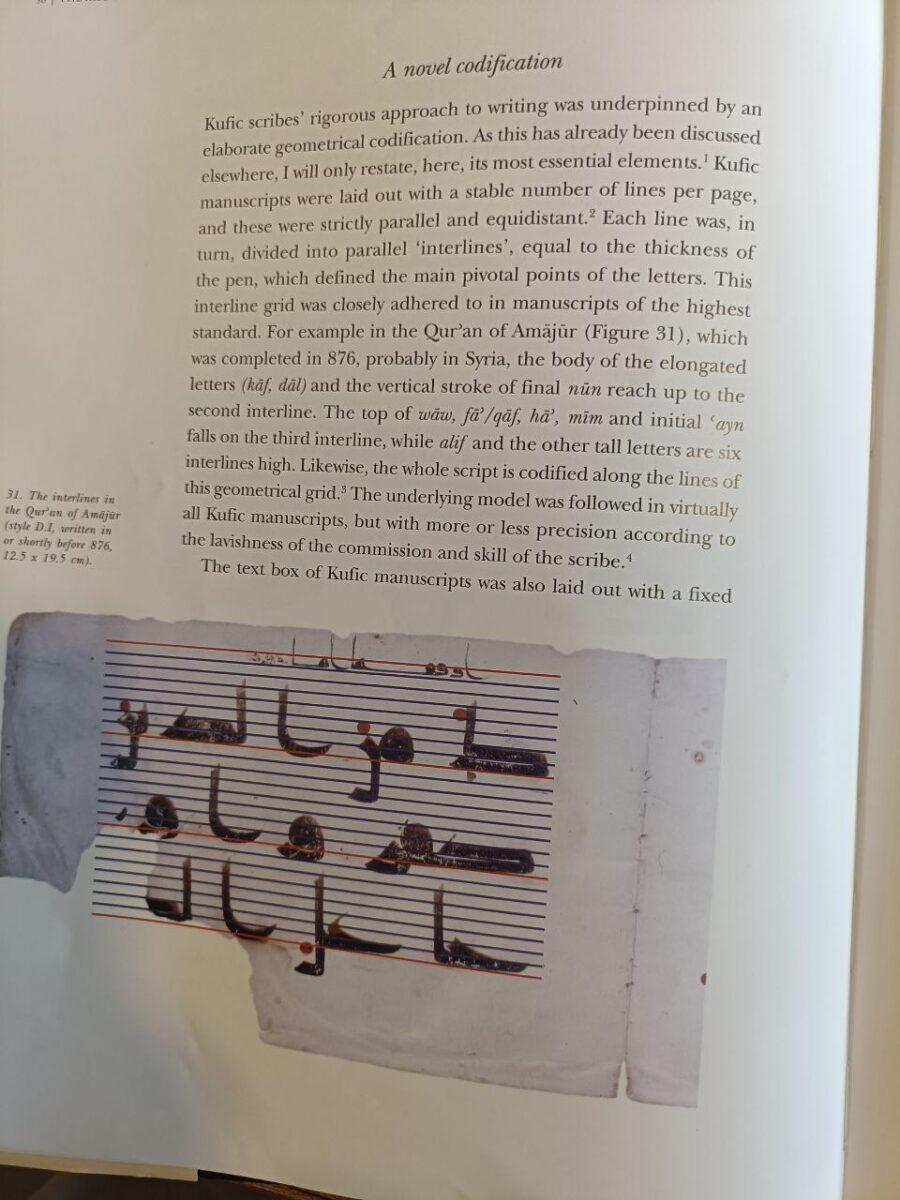

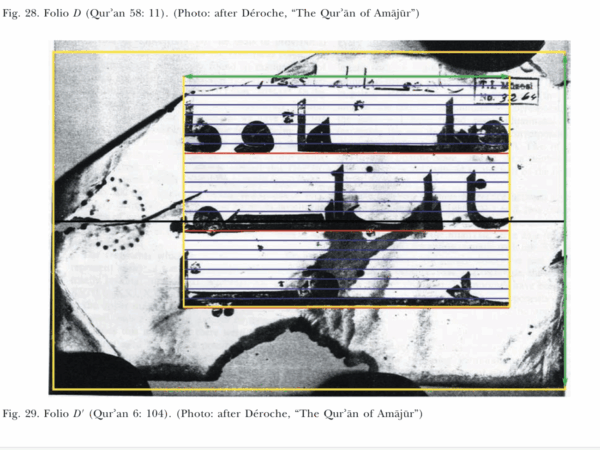

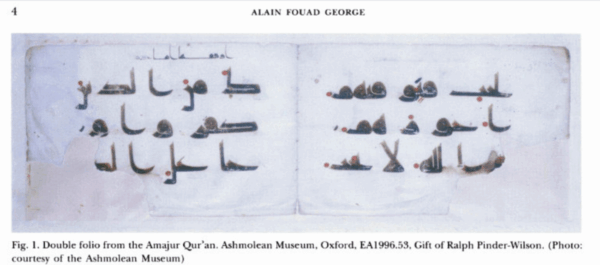

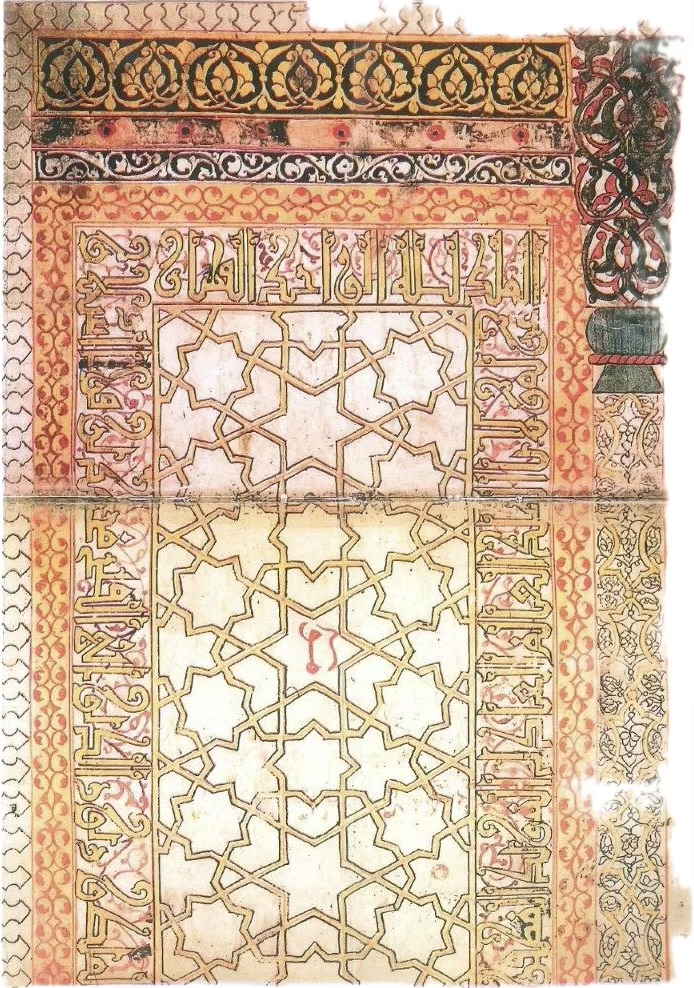

Amajur Qur`an

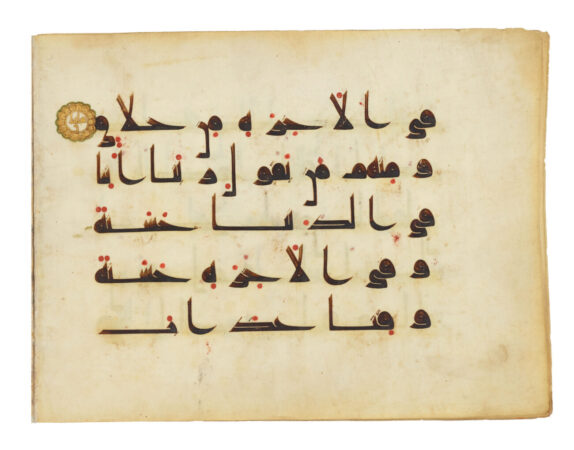

2. Kufic Calligraphy as the Embodiment of the Sacred Word

The substance of Kufi calligraphy transcends its material structure or symbolic letters because it was the embodied face of the sacred word, the manifested face of the sacred revelation of the Qur’an. As if it were the incarnation of the sacred Word of Allah, it was the first materialized form of the Qur’an. And Qur`an itself could be considered as some recitations from the verses of Lawh Mahfuz (the Preserved Tablet). And the Qur’an’s mediating role between the human heart and Allah—that is, the soul of the Qur’an—had been embodied by the Kufi script. According to Qur’anic revelation, writing is not merely a record but a manifestation—an embodiment—of divine knowledge. As expressed in the aforementioned epigraph, in the very first verses of the Qur’an:

“Recite in the name of your Lord who created—Created man from a clinging substance.Recite, and your Lord is the Most Generous—Who taught by the pen—Taught man what he did not know.” (Qur’an, 96:1–5)

The “Pen (al-Qalam),” as described in this verse by the Qur’an, is not only an instrument of writing but of divine instruction. Here, the Pen is not merely a tool for writing but a sacred symbol that records knowledge beforehand, foreseeing and instructing it to come alive later, to come into the act of creation.

In fact, the Qur’an itself instructs us to begin with God’s name and commands human beings to learn, to read, and to pursue knowledge. It is an interesting mixtum compositum that creation, knowledge, and writing are all mentioned together in the first verses of the Qur’an. Human existence, the capacity for learning, and the act of writing are intertwined in a singular ontological structure here. And the name of the revelation itself, “The Qur’an,” means ‘to be recited,’ implying that meaning itself is revealed in the heart of the words, apparently materialized and represented as Kufi script, and then becomes alive when it is recited as the Qur’an.

3. Preserved Tablet (Lawh Mahfuz) and Qur’an

Once, I wrote a poem about the Unity of God in my Divan (Şeydâ Dîvânı, Tevhid Kasidesi), and there is a stanza in that poem:

Ma’nâ yı-kelâm şâhid i-mazmûn i-Hudâdır

Gönlüm sadefinden olur azrâ gibi peydâ

“The meaning of the word professes the hidden existence of God in it”

This word, likewise a virgin pearl, occurs in my heart which is the mother-of-pearl.”*1

How is it possible that some strange sounds of a word might include a “meaning,” and that word’s meaning can imply the hidden existence of God as Meaning? Here, Nature holds a material face of existence like the sound of a word, but nature also has a hidden meaning in it, like God. That is, God is the meaning of existence. Thus, unlike nature’s physical/material mode, there is also a metaphysical mode of nature. Nature’s physical face hides that sacred mode of meaning within it, just like a pearl in a shell.

This ontological framework highlights the metaphysical question of representation—how truth is made manifest. Here, the Qur’anic concept of the Lawḥ Maḥfūẓ (Preserved Tablet) becomes pertinent. The Qur’an itself, as a timeless text, is said to be inscribed on the eternal tablet:

بل هو قرآن مجيد في لوحٍ محفوظ “Indeed, it is a glorious Qur’an, In a Preserved Tablet.” (Qur’an, 85:21–22)

Here, the Lawḥ Maḥfūẓ/Preserved Tablet is understood as the cosmic ledger of divine decree, destiny, and knowledge. In this context, writing is not merely a communicative tool but a metaphysical register. The transcription of the Qur’an into written form does not reduce its timelessness; rather, it translates the eternal into the human realm of comprehension. Here, Kufi script serves not only an ontological but also a theophanic function, as its drawn signs reflect and embody the incarnation of meaning through words.

Islamic scholars have addressed these themes across theological, linguistic, and philosophical dimensions. Linguists such as Ibn Fāris and Ibn Jinnī maintained that language and writing possess a divine origin, grounding this belief in the verse:

وَعَلَّمَ اٰدَمَ الْاَسْمَٓاءَ كُلَّهَا “And He taught Adam the names—all of them…” (Qur’an, 2:31)

Indeed, according to the Qur’an, human language was also taught to Adam by God; thus, language is not a conventional communication instrument made by humans. This verse refers not solely to vocabulary acquisition but also to the naming of meanings, concepts, and even realities. Accordingly, writing is not simply a human invention but part of the ontological continuity of divine instruction—a vehicle of revelation, an embodiment of meaning, and a visible form of truth.

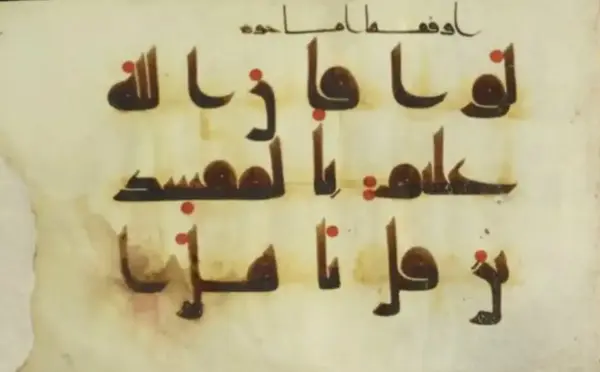

اِقْرَأْ وَ رَبُّكَ الْاَكْرَمُۙ اَلَّذٖي عَلَّمَ بِالْقَلَمِۙ Recite: And thy Lord is the most Generous, Who taught by the Pen Taught Man, that he knew not Qur’an/ The Blood-clot

Writing, in this view, is not a creation but a tajallī—a divine manifestation.

4. Semantical debates abot the origine of language and naming

Orthodox (Sunni) Muslims believe that the Qur’an is the Word of God brought by Gabriel to the consciousness of Muhammad; and being so, the Qur’an is the incarnation of the word of God and has no beginning in time, similar to the guarded scripture (Lawh Mahfuz). Because of this Lawh Mahfuz, which is a metaphysical guarded book and includes all events from the beginning until Doomsday, a theological problem naturally arises: predestination. In that case, how can we have free human volition? If it is the Word of God brought by Gabriel to the prophet, is this word, the Qur’an, created in time or not? For it is revealed from what God, who created everything else beforehand, with the Pen (Qalem), from the Guarded Book (Lawh Mahfuz). Even the name of revelation, i.e., “Qur’an,” means reading aloud, reciting; the name does not designate a book in the usual sense. Perhaps it could be understood as reciting some verses from Lewhi Mahfuzas revealed to the prophet’s consciousness. That is why the first word of the Qur’an is Iqra/Recite. And what about the nature of revelation as a mystical experience of the Prophet, is it an altered state of consciousness? How and why did he organize his believers to establish a ‘theonomous order’ which tied them by both faith and politics? Why the Qur’an does not have a usual book format, and why the prophet did not ask his ‘scripts of revelation’ to write down all the verses of the Qur’an regularly in a book format? All these and many similar questions are also discussed by various theologians of Islam, beginning from the first century of Islam. Why are the language, and even writing, regarded as not created by humans but God-given to Adam, according to some medieval Islamic scholars?

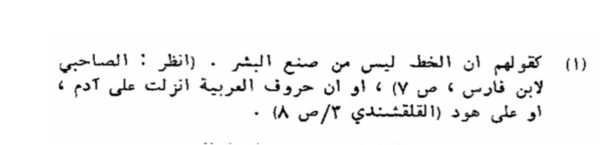

For example, Ibn al-Faris says that ‘no doubt the script is not an artwork (sun’u) of humanity,’ meaning it is not man-made. And according to Qalqashandi, Arabic letters were also revealed to Adam or prophet Hud.

This reminds me ancient Egyptian belief that writing invented by God. I wil add that anecdot to the annexes.

According to this view, writing is not merely a tool of communication but an extension of revelation and contemplation. It is the visual embodiment of the divine attribute of Speech (Kelām/Logos). If writing stems from a divine source, then letters and symbols do not simply signify meaning—they embody and transmit it. Each grapheme becomes a theophany, not merely a sign. Alternatively, if writing is a human construct, then letters and symbols are arbitrary indicators whose meaning is produced through consensus and context.

Muhammed Antakî says in his book el Vecîz fî Fıkh ül-Lüga (p).25-27* 2 that because of the above-mentioned verse of the Qur’an, ‘He taught Adam all the names (وَعَلَّمَ اٰدَمَ الْاَسْمَٓاءَ كُلَّهَا), some Muslim scholars say that language itself is not created by humans but taught to Adam by God (Tevkîfî). According to some other Muslim scholars—who also quote other Qur’anic verses—language came into existence culturally made by humans (bi’t-tevatu).

Within this Islamic intellectual tradition, this inquiry has largely revolved around the question of whether language is of divine origin (tawqīfī) or a human invention (isti‘lāḥī or taʿātī); yet, this issue is not merely a philosophical curiosity but an epistemological question that directly informs the meaning of writing itself—especially sacred writing in Arabic—and, by extension, the semantic depth of the Kufi script.

According to Muhammad Antaki, such debates are not exclusive to Islamic thought. In Western philosophy too, the same question arises. The quest for the origin of language begins in ancient Greece with this question: ‘Is a name’s designation to the reality of a thing created by humans with convention or does it come from the nature of man?’ (Is it taught by God to Adam?) According to Heraclitus, language/logos is not made by humans; that is, the name signifies the named thing naturally. According to Democritus, it is made by humans; language also, like all other man-made elements of culture, is created by conventions between people.

Plato’s Cratylus famously stages the conflict between the view that names are “natural” (phýsei) and the view that they are conventional (thései). Do names reflect the essence of things, or are they arbitrary? This remains a central concern in modern philosophy of language. While Plato leans toward the idea that some names may be inherently appropriate, the nominalist tradition would later dominate Western discourse, with thinkers such as John Locke, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Saul Kripke reconceiving the relationship between words and meaning through frameworks of mental representation, social usage, and linguistic practice. This dispute continues in Western philosophy until now, but it is not necessary here to quote what other Western philosophers say about this matter.

As transmitted in the book Fıkh ul-Luga (semantics), Ibn Faris also says that Arabic language is tevkîfî (God-given) according to the aforementioned verse of the Qur’an that states God taught Adam all the names. Ibn Faris does not only provide this kind of evidence (naklî), which is based on Qur’an verses, but also offers a reasoning (aklī) argument: “because we do not know any example of giving a name to something by the people who lived in the recent past; also we did not hear that companions of the prophet made new names or terms…” Yet the majority of Muslim scholars say that the ‘origin of the language is tevatu’ (by convention) and language is istilah (terminology); it is not made by ilham, vahiy (revelation), or tevkîf (God-given)’. For example, Kadı Ebubekir al-Bâkıllânî says that both are possible: “inne t-ta’lim kad husile bi’l-ilhâm ey bi’l kuvveti, lekad vadaa allahu fi’l-insân meleketü’l halk, sümme terekehu yahluku alâ hevâihi” which means “Adam learned by revelation, that is, language is God-given; or God gave to man the ability to create and left him to create as he wishes.” Abū Bakr al-Bāqillānī and some other scholars also mentioned the possibility that writing could have been developed gradually as a product of social convention and human intellect. According to this view, writing arises not from a sacred origin but from rational necessity and human adaptation. It is not tawqīfī (divinely fixed) but ta‘ātī(emergent from mutual human exchange). *3 This dichotomy over the origin of language has profound implications for the relationship between writing and meaning.

Indeed, this is a universal philosophical question about meaning and representation. In fact, this is a difficult subject in semantics, and I know it cannot be fully expressed with a few simple statements. For instance’ in 1892, in his brilliant analysis of language `On Sense and Reference`, Gottlob Frege states that any name as a sign for something is not only a reference to something, i.e., evening star, but also includes a sense: for example it is also named morning star and is both names refer to Venus Planet not a star in fact. If you say, for example the evening star is the evening star` and it has an astronomical sense which means Venus Planet. Then John Searle speaks about `Proper Names‘saying that some clusters of meaning attributed to referred subject by a name. Then, Saul Kripke comes and makes extensive semantical and logical discussions about ‘naming’ in his book `Naming and Necessity`. I will not delve here into the semantical discussions but only mention here these contemporary logical and semantical arguments about naming by simply extracting an interesting excerpt from Saul Kripke:

‘Sometimes we discover that two names have the same referent and express this by an identity statement. So, for example, you see a star in the evening and it’s called ‘Hesperus’ (evening star). We see a star in the morning and call it ‘Phosphorus’ (morning star). Well, then, in fact we find that it’s not a star, but is the planet Venus and that Hesperus and Phosphorus are in fact the same. So we express this by ‘Hesperus is Phosphorus’…Also we may raise the question whether a name has any reference at all when we ask, e.g., whether Aristotle ever existed… what really is queried is whether anything answers to the properties we associate with the name—in the case of Aristotle, whether any one Greek philosopher produced certain works, or at least a suitable number of them.’ *4

Kripke’s famous example—the dual naming of the planet Venus as Phosphorus(morning star) and Hesperus (evening star)—exemplifies the complexity of reference and naming. Although the two names refer to the same celestial object, their different usages suggest distinct epistemic paths. This complicates the question of whether writing merely reflects reality or actively constitutes it. The act of naming—and by extension writing—is not merely descriptive but generative of meaning.

There is an interesting semantical saying of Alfred Korzybski in his book “Science and Sanity”, “the map is not territory”; and his student Hayakawa also says in his book “Language in Thought and Action” that “words can not be decribed by words”.

In fact, I imagine that it is possible to discuss in this context Leibnitz’s law of identity and `identity of indiscernibles`, but I do not wish to delve more deeply into the philosophical implications of Qur’anic verses. However, I must warn that words or names may imply much more than their seemingly apparent and clear meaning. Indeed, words and names may imply much more difficult, problematic philosophical matters than they have been understood by people in their traditional usage in language. And so, sometimes they even transcend the capacity of human reasoning. I do not wish to debate any human belief here, so I will not discuss Leibniz’s law; but I suspect that, if I could dispute this idea of the “identity of indiscernibles” of Leibniz in a large context, not only naming but even the identity of the named things also could seem dubious.

Let me remind here that identity is the first principle of logic, i.e., “a thing is what it is”; other rules of logic are also derived from this identity principle; and being so, all logical human reasoning depends on the identity principle. The most satisfactory statement of identity was indeed, “ego sum qui sum,” which is said to Moses on Mount Sinai according to the Old Testament (Genesis II, 13). *5 This also means the absolute identity (God) which never changes or dies (huve l-baqi). Yet scholars, especially theologians, do not understand that human knowledge, language, and the reasoning capacity of humanity are not capable to answer every problem of truth we encounter.

Let us remember that, in the 20th century, semantics logic and mathematics are intertwined as a tool of rational reasoning. As a mathematician, Alfred Tarsky wrote truth tables for the truth values of sentences. In addition, we have not only one criteria of truth as coherence theory of truth` but also we have correspondence theory of truth, performance theory of truth, pragmatic theory of truth, sentential theory of truth etc. There are many criteria of truth theories, yet I also add a criteria, a con-spective/ holistic theory of truth.

As I already said, within Islamic thought, these philosophical concerns converge on writing. Kufic script, in this regard, is not merely a stylistic choice but a material manifestation of the sacred ontological and theological dimensions of writing. It is not meant only to be read but to be contemplated, visualized, and intuitively grasped. I will repeat here a beautiful saying of Hallâc: “Truth is true only for itself!”

But I do not wish to discuss those names ‘Qur’an (recitation), Kitabu meknûn/Levhi mahfuz (kept and guarded book) with all their historical and theological implications, i.e., the predestination/fate problem or the role of man in the actions of historical events. After all, this is an essay about Kufi calligraphy, not particularly theology or the “sacred scripture Qur’an itself.” I wish to repeat here a couplet:

“Kad şâ’e bi sun’ihi beyâneh

Mâ azamü fil bekâi şāneh”

“Indeed, He has willed its exposition through His craftsmanship.”

This line evokes divine intentionality—suggesting that the act of creation itself is a form of revelation. How magnificent is His affair in eternity.”

5. Theological and Cosmological Significance of Kufi Script, Letters as Theophanies in Islamic Thought

Thus, in the early centuries of Islamic civilization, Kufi calligraphy was not only a mode of writing but also a metaphysical structure through which the sacred was represented. It served as a conduction channel for transferring revelation into spatial and temporal registers. It is the symbolically embodied aspect of articulating metaphysical truths as revealed by the Qur’an.

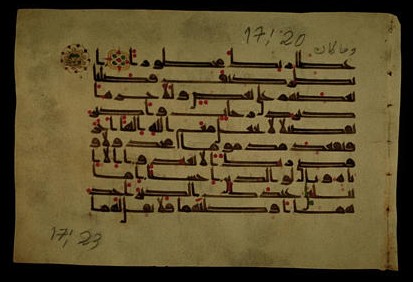

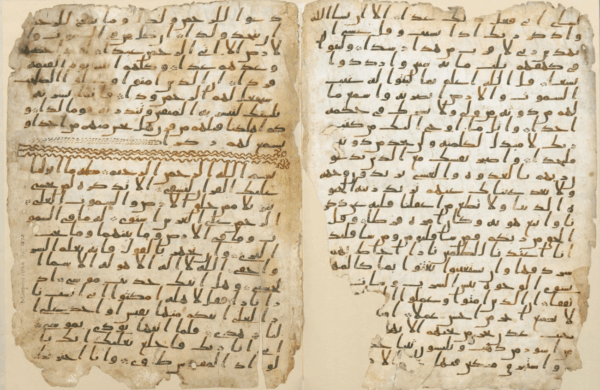

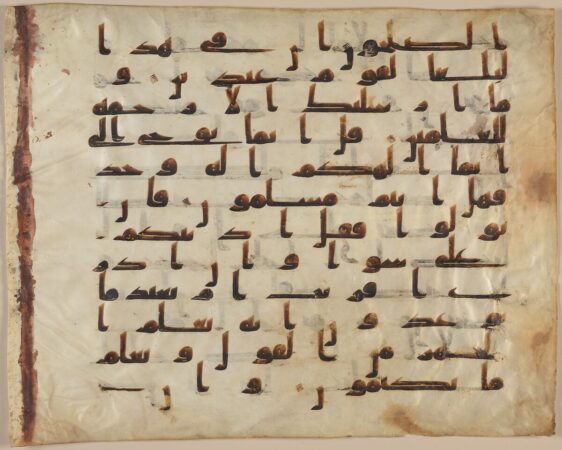

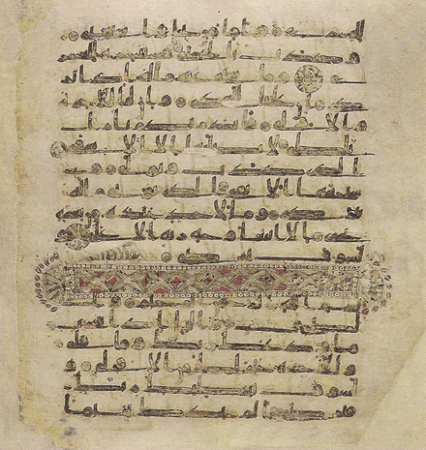

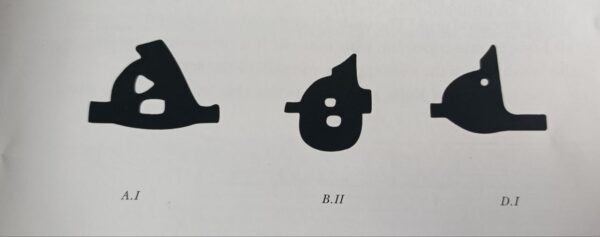

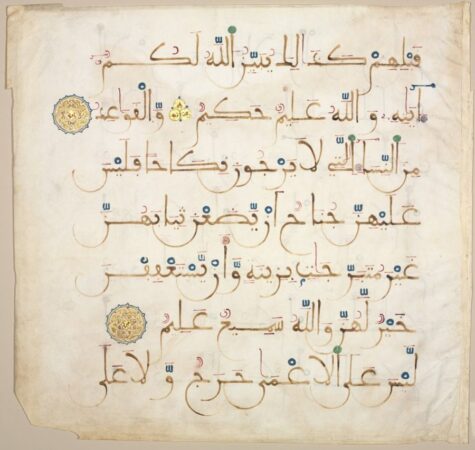

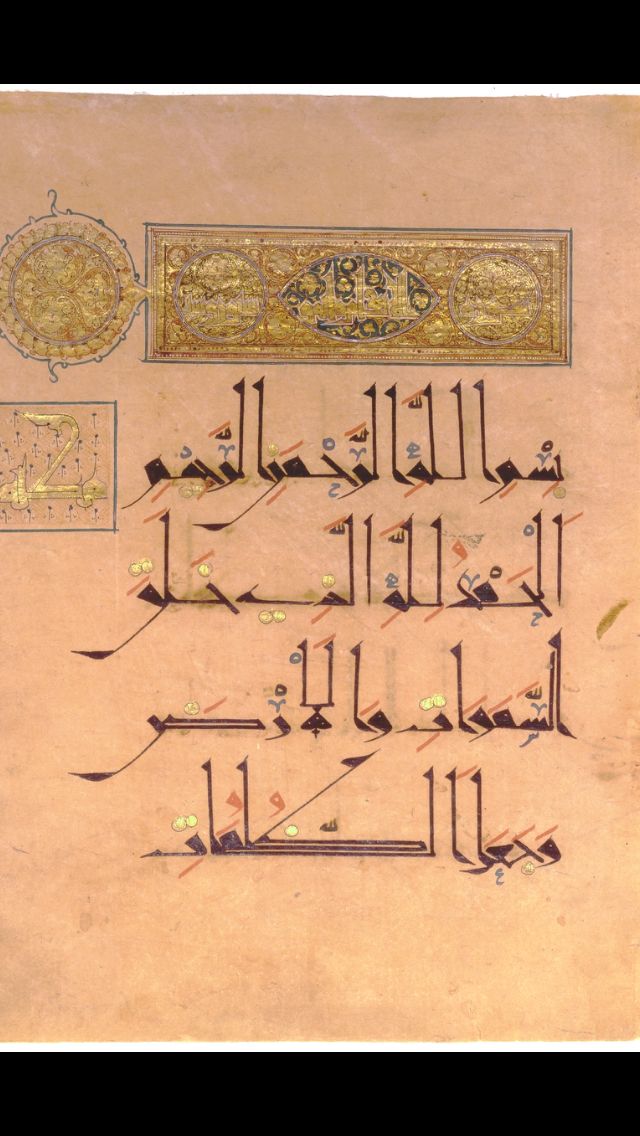

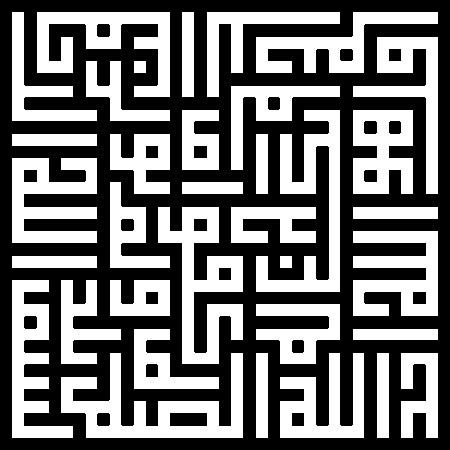

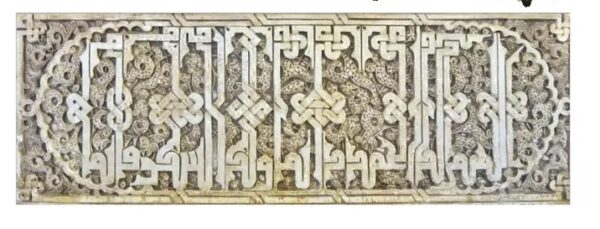

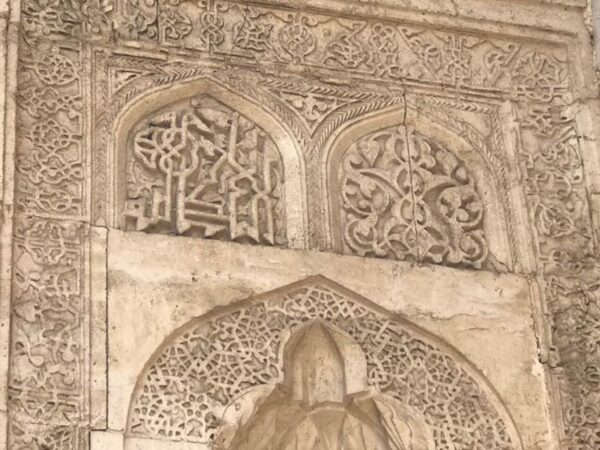

The usage of Kufi script in the earliest Qur’anic manuscripts enabled a strong identification between the form of writing and the content it carried. Besides, writing a Qur’an manuscript was not an easy task in the first century of Islam, because there was no paper then, and calligraphers were forced to write a few verses on large pages of parchments; Qur’an manuscripts were made from hundreds of sheepskins. Certainly, this material also had a significant impact on the minimalist and angular style of the Kufi calligraphy of the Qur’an. Within this framework, the geometric composition of the script might be perceived as a visual symbol of divine mystery. Its symmetrical balance of vertical and horizontal lines seems to reflect the divine order embedded in the universe. The space between letters and the proportional heights and widths of letters were functional features—but they also became revered as part of a sacred style that reinforced the sanctity of the message.

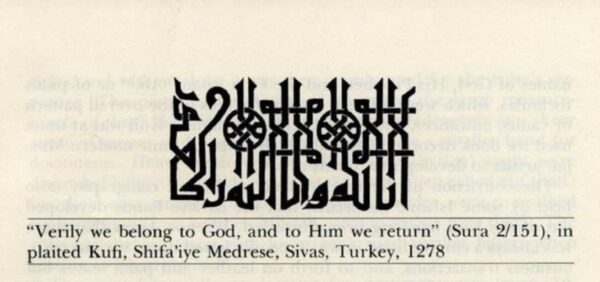

Let me remind here Ibn al-ʿArabī’s theory of the “ontology of letters,” which is especially illuminating. According to Ibn al-ʿArabī, every letter is a theophany—an outward manifestation of one of the metaphysical realities contained in divine knowledge. Letters are not accidental phonetic tools; they are expressions of divine being. Writing becomes a surface upon which these theophanies appear. The fixed geometric nature of Kufic script shows its ontological and metaphysical charge more visibly potent.

Ibn al-ʿArabī says: “All praise be to Allah, who instills meanings into the heart of words.” For Ibn al-ʿArabī, all letters are symbolic representations of God’s creative act. A letter is not merely a sound unit but the primordial shape of a being. Ibn al-ʿArabī’s theory of letters elevates this discussion to a mystical plane. In his thought, letters become the metaphysical building blocks of existence, each reflecting an aspect or attribute of the Divine Names. *2

”In his Art of Islam, Titus Burckhardt maintained that ‘it can be said without fear of exaggeration that nothing has typified the aesthetic sense of the Muslim peoples as much as the Arabic script’.17 While the term ‘calligraphy’ comes from the Greek words for beauty (kallos) and writing (graphein), Ibn ʿArabī’s meditations on the topic extend well beyond the properties of elegant handwriting. In Sufi circles, calligraphy was perceived as a technical science which involved the production of letters in accordance with the strictly defined geometrical ratios, strokes and angles – each of which is imbued with symbolic meanings. Firm in the belief that proficiency in calligraphy can lead to familiarity with the meaning of letters, Ibn ʿArabī analysed the orthographic forms of letters with geometric precision. By means of calligraphy, his notions of the ideal shapes and the meanings of letters are directly put into practice. In order to come to terms with Ibn ʿArabī’s meditations on the orthographic structures and the symbolic values he attributed to them, special attention will be given to the twenty-seven holographs and the several dozens of surviving autographs in Ibn ʿArabī’s own hand.” *3

As if, the architectural form of Kufic script embodies a belief that letters carry a metaphysical essence. Kufic calligraphy solemnly displays and suggests the aesthetic and visual expression of this reverence for the sacred words.

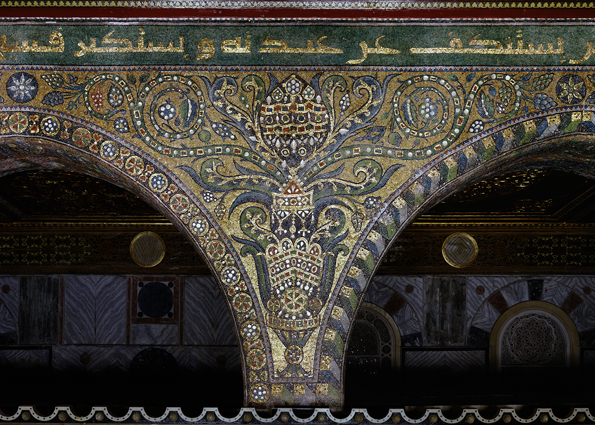

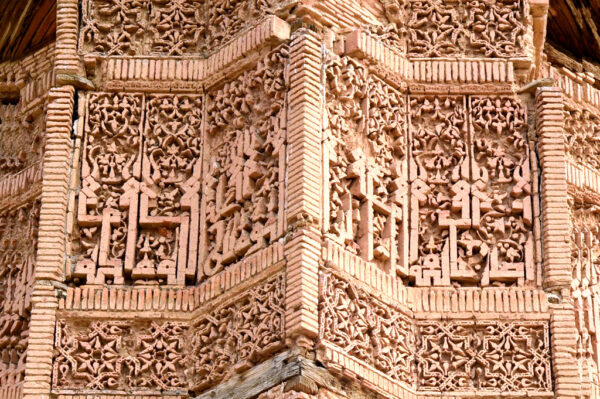

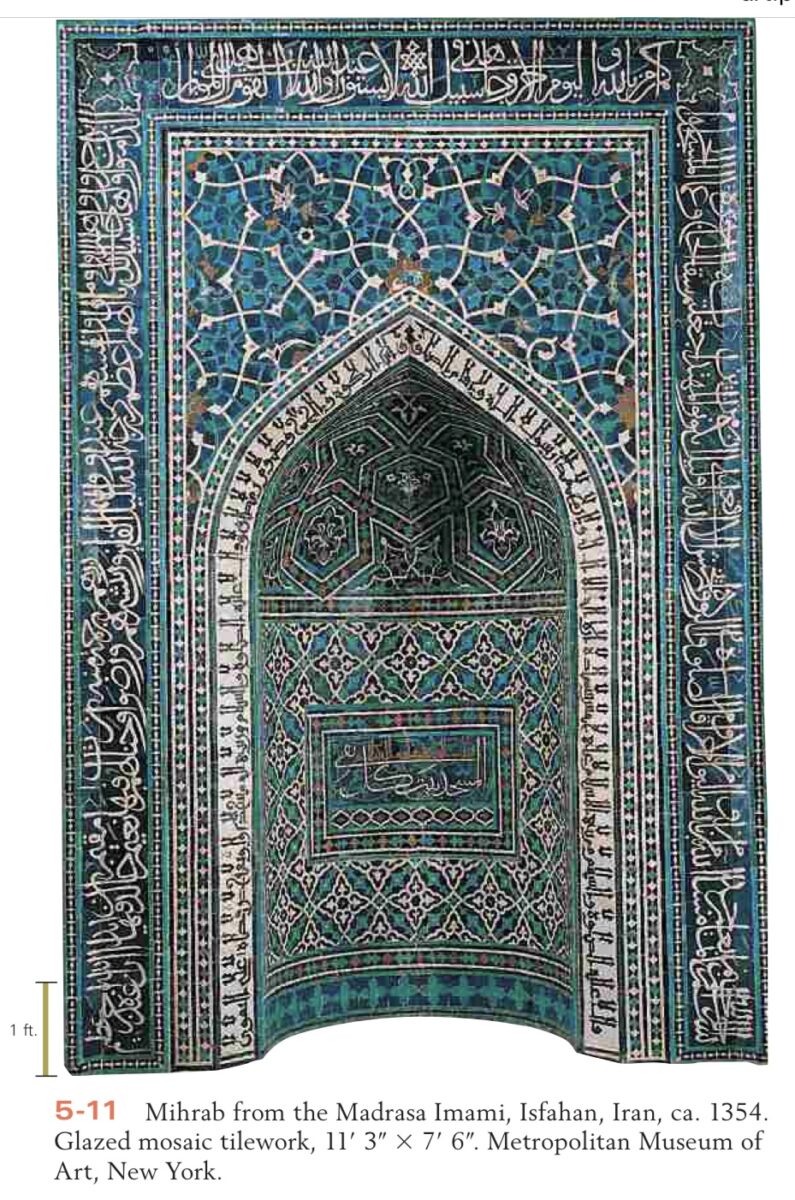

These theological implications of Kufic script are not confined to the shapes of letters alone. The materials with Kufi inscriptions or the space it occupies, like a mihrab, also contribute to its semantic richness. Qur’an verses written in Kufic script are not only vehicles of oral transmission but also served as visual representations of divine revelation. Some Qur’anic verses in Kufic script were often integrated into architectural surfaces—thus merging revelation with space and amplifying the symbolic power of the script.

This intermingling of writing with cosmic order is implied by Qur’anic verses such as the opening of Sūrat al-Qalam:

“Nūn. By the pen and what they inscribe.” (Qur’an, 68:1)

Here, The Pen is not an ordinary object but, as aforementioned, it is the first creation of God, inscribing divine decree and order into existence. Hadith traditions also affirm this interpretation, stating that the first thing God created was the Pen. Here, writing signifies not only knowledge production but also the act of inscribing destiny and existence.

Kufic calligraphy, according to this cosmological symbolism, seems both static and dynamic. It appears majestic and static in its geometric fixity, but also dynamic because it embodies revelation and continually acquires new layers of meaning in time. Its static form suggests permanence, but its dynamic semiotic potential emphasizes the timeless relevance of the sacred message.

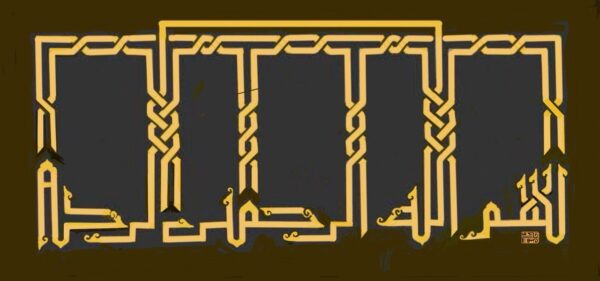

Moreover, the structural design of Kufic script could imply a reverence for an aesthetic feeling that aligns closely with the Islamic concept of tawḥīd—the oneness and unity of God. Its repetitive, proportionate, majestic visual character, commonly used on important buildings, makes Kufic calligraphy an aesthetic affirmation of divine unity and also an identity symbol of Islamic civilization. Each letter occupies a specific place in this visual cosmos; nothing is arbitrary. In such a way, Kufic script becomes a visual and symbolic articulation of tawḥīd at both the formal and conceptual levels.

It truly occupies a distinctive position within this representational framework. Its geometric construction produces a space where form and meaning meet. Its solemn and majestic abstraction invites not only textual reading but also intuitive contemplation. Kufic does not assert meaning directly; it intimates, alludes, and beckons the observer toward a metaphysical horizon.

As if, Kufic script visually expresses the belief that letters are not just phonetic units but ontological entities. Al-Ḥallāj’s dictum—“Letters are bodies, meanings are their souls”—resonates here as a metaphysical hermeneutic.

Kufic script, then, does not merely transcribe a text—it transmits the very structure of its meaning. The ratios between letters, their symmetrical layout, recurrence, and internal logic are not simply visual choices but reflect an architecture of meaning. Kufic is simultaneously a bearer and producer of meaning, an aesthetic system through which ontological truths are encoded.

This understanding of Kufi calligraphy marks it as a unique expression of the Islamic conception of the relationship between writing and truth. While preserving sacred content, it also suggests that meaning is not static but always subject to reinterpretation. Kufi`s formal rigidity offers a visual anchor through which shifting interpretations may gain stability.

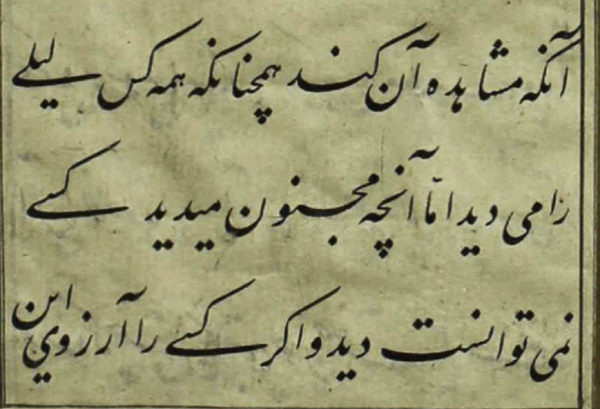

The calligrapher who wrote the book `âdâb ul mashk` (practice etiquette of callıgraphy) had said in that book about understanding the calligraphy that: “hemçünân ki heme kes Leyli râ mîdîd emmâ an çi Mecnûn mîdîd kesî nemîtuvânest dîd” (for instance, everybody sees Leyla but what Mejnoun sees in her noboody is able to see).

6. Scripture as Witness

Thus, Kufic calligraphy embodies the sacred, provokes reflection on meaning, and channels metaphysical resonance. In the silence of its letters, one hears the echoes of a vast cultural and theological vision. It is not just a calligraphy—it is a metaphysical architecture, a form of thought, and a sanctuary for meaning.

This is why the versatile symbolism of Kufi script appears so often in Islamic architecture. It usually adorns domes, mihrabs, or arches, making Kufi an act of devotion, contemplation, and transmission of knowledge. Kufi inscriptions of sacred texts onto architectural surfaces show, within this uniformity of style, becomes a symbol of tewhid (unity of Allah), a bearer of the unique meaning and identity of Islamic civilization.

That is, Kufic script manifests the integral interrelationship among knowledge, revelation, destiny, and aesthetics in Islam. Its geometric form implies cosmic order; its metaphysical dimension transforms letters into symbols of being. Kufic calligraphy is not merely writing—it seems as if it is the embodiment of theological truth and a sacred way through which the unseen is made visible.

In conclusion, debates over the origin of language and writing are not merely historical but ontological and epistemological in nature. Kufic calligraphy stands at the center of this discourse: it embodies the sacred, provokes reflection on meaning, and channels metaphysical resonance. In the silence of its letters, one hears the echoes of a vast cultural and theological vision. It is not just a calligraphy—it is a metaphysical architecture, a form of thought, and a sanctuary for meaning.

This is why the versatile symbolism of Kufic script appears so often in Islamic architecture. It usually adorns domes, mihrabs, or arches, making Kufic an act of devotion, contemplation, and transmission of knowledge. Kufic inscriptions of sacred texts onto architectural surfaces show, within this uniformity of style, that space itself becomes a symbol of tewhid (unity of Allah), a bearer of the unique meaning and identity of Islamic civilization.

That is, Kufic script manifests the integral interrelationship among knowledge, revelation, destiny, and aesthetics in Islam. Its geometric form implies cosmic order; its metaphysical dimension transforms letters into symbols of being. Kufic calligraphy is not merely writing—it seems as if it is the embodiment of theological truth and a sacred way through which the unseen is made visible.

On the other hand, there is a striking similarity between levh-i mahfuz/guarded plate/preserved plate (from which the Qur’an is also understood as reciting some verses revealed by archangel Gabriel to prophet Muhammad’s heart) and contemporary simulation theory and practice. According to Qur2an, Levhi mahfuz guarded tablet and Pen comes before existence. As if, this writing act resembles the contemporary practice of writing some algorithm codes for a computer game that later comes to life whenever you wish to play that game. Indeed, those verses of the Qur’an about the guarded tablet (levhi mahfuz) remind me of contemporary discussions about whether this universe, existence, is real or a simulation, or what not. As is known, some virtual reality games are only written algorithms; they are written by a code-script and become alive to be seen and played in computer games on a screen. Nowadays, some physics theorists seriously argue that the universe could be a simulation written and played like those virtual reality games. Surely, it could be thought so, metaphorically or seriously; and it is interesting to see that what the Qur’an describes as Pen and Guarded Scripture (levhi mahfuz/kitabu meknûn) articulates exactly the same idea: God created the Pen, and the Pen wrote all events from the beginning to Doomsday. That is, like a virtual game, what happened in this universe is written/or coded and predestined in that guarded book (levhi mahfuz/kitabu meknûn), and then all events happen according to the codes of that guarded-book which means our universe is only a simulation. There should be a real existence but this world is not real; it is just like a virtual game, a virtual reality.

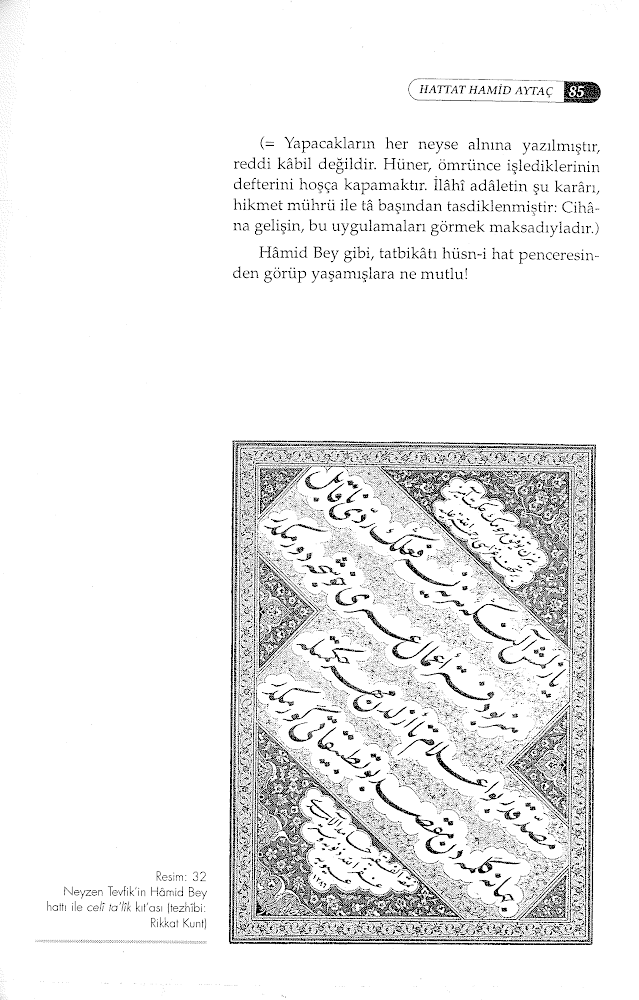

Anyway, because of the belief about the aforementioned Levhi Mahfuz/guarded book, the same simulation metaphor was used by a Turkish poet as well. I will include the calligraphy of Neyzen Tevfik’s poem, which says:

“Whatever is written on the forehead of the deed, its rejection is impossible; Skill is to neatly fold this book of life’s deeds. This declaration is confirmed with the seal of wisdom from eternity; The purpose for coming into the world is to witness these practices.” (Yazılmış alnına her neyse fi’liin, reddi nâkaabil/ Hüner, bu defter-i âmâl-i ömrü hoşca dürmektir Musaddaktır bu î’lâm tâ ezelelden muhr-i hikmetle/Cihâna gelmeden maksad bu tatbikâtı görmektir)

We already know from neurophysiology and consciousness studies that what we perceive as the world or existence is not the real world but a simulated picture made by human consciousness. As metaphorically explained by Donald Hoffman, human consciousness is like a computer interface, offering a simplified but useful description of the world. I recall here, Edgar Allan Poe’s beautiful poem where he says:

`All that we see or seem

Is but a dream within a dream.’

chapter two

Critical evaluations of disciplines and my philosophy of history

1. epistemological evaluations and perspectives

We have spoken about the prophetic revelation of the Qur’an and its theological implications, but what about ordinary methods used by humankind in the search for wisdom? For a gratifying understanding of an investigation, one must be aware of different perspectives imposed by different standpoints. Especially’ since Kufi script itself is the most common and identifying facet of Islamic culture, a multidisciplinary approach is necessary to grasp the full implications of this subject. I am writing about the significance of Kufi Calligraphy and my philosophy of history. That is, a larger framework of understanding provided by a con-spective/holistic philosophy of history. However, to adopt a holistic perspective means one must try to grasp meaning in a different light with every different standpoint; in this case, this discourse becomes too expansive and would include every important aspect of human thought and destiny.

I cannot express here all of my philosophical ideas in large; but I will make some short remarks in this context, at least to give an idea about my understanding of existence and my philosophy of history in general. Yet I will add some of my previously written articles as annexes to this essay. So that, what I say here about some points of the discussed subjects abruptly in short as my philosophy of history, At least, some of these ideas, could be seen in a larger context in these annexes. It is because I am writing not only about kufi scripture but also about my philosophy of history interpreting some facets of historical Islamic Culture from my perspective.

~Ars longa vita brevis~ So for now, I will try to define, as briefly as possible, my classification of different standpoints and the varieties of explanatory perspectives used by humanity in the search for wisdom. In my judgment, there are seven pillars of wisdom, that is, seven ways of constructing perspectives as different kinds of interpretation in search of understanding. I believe my classification of these different perspectives can determine the method and content of disciplines as differing viewpoints for making sense of their content, according to the specific perspective each belongs to. Thus:

- The viewpoint of History is retrospection (retro-spectare, retrospective).

- Science is prospection (pro-spectare/prospective).

- Philosophy is inspection. (in-spectare, inspective)

- Art is introspection.. (intro-spectare, introspective)

- Mystical experience is introspection by illumination.

- Religious wisdom also provides a perspective for orientation.

- And Philosophy of History should adopt a holistic perspective; that is, it should take into account all of these different perspectives, striving to merge them as a holistic “con-spection.” (con-spectare)

The purpose of my classification of disciplines according to special perspectives, is to show the limits of the capabilities of every discipline due to its differing perspective and limited angle of its standpoint. In short, every kind of knowledge or understanding should recognize that there are many different perspectives for making sense of a subject. All of these understanding styles need to be filtered, re-examined, and re-evaluated by a holistic philosophy of history con-spectively for true understanding. So be it! And this is why I am trying to comprehend all aspects of Kufic script from this holistic perspective of my philosophy of history.

However, according to my philosophy of history, not only are these perspectives of understanding and human reasoning tools considered limited ways of comprehension, but human understanding of reality itself is also a narrow angle, originating from the standpoint of humankind’s “consciousness-capacity.”

I will remind now a couplet from Fuzûlî :

“Şuğl i-acebî girifteem pîş

Pîş ü pes -i o temâm teşvîş”

“I’ve become entangled in a strange occupation—

Its beginning and end are nothing but confusion.”

2. The Limits of Human Consciousness

Perhaps I need to elaborate a little more on human consciousness, because what we know about any culture, or what we enjoy or dislike in the world—all knowledge depends on our consciousness. And there are many unsolved facets of human consciousness. Later come the semantic problems of human languages, and also the problem of knowledge and the defects of human reasoning. Yet, despite humankind’s limited ability to comprehend, we must make sense of our studies, taking into consideration every different perspective about the nature of the subjects studied, as far as possible within the limits of human abilities. Later comes the evaluation of those mentioned seven disciplines and the epistemological value of human knowledge in general. In my understanding, a philosophy of history should provide a holistic understanding of wisdom to attain an orientation and a projective vision of the future about the destiny of humankind, if it is to be fruitful.

There is this verse in The Bible, Corinthians 13:11: “Videmus nunc per speculum in aenigmate: tunc autem facie ad faciem. Nunc cognosco ex parte: tunc autem cognoscam sicut et cognitus sum.” *1 “For now, we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known.” This verse was rephrased by St. Jerome, who said: “per speculum videmus in aenigmate; et ex parte cognoscimus, et ex parte prophetamus”; that is, “we see in an enigma through the looking glass in the dark: we comprehend in part, and in part we prophetize to foreshow events.” In fact, this is a statement that compares knowledge and belief. But consciousness also reflects reality just like that. My consciousness is the mirror of my mind, and reality comprises enigmatic light rays reflected by the eye to the mirror of the mind, but they are reflected only in part—i.e., only visible light frequencies between 400-800 nanometers. Indeed, most of the photons of visible light are again filtered twice by the two layers of the retina of the human eye. Then they are processed as ionized electro-chemical events separately by so many brain neurons to be finally perceived as movement, color, shape, etc. And then these partial sense data are united and constructed by the mind as the picture of reality. In such a way, we are made aware of this enigma of the world in our speculum mentis, within the mirror of the mind. It is clear that the mind cannot directly touch that enigmatic reality itself, but the mind can only build an impression of reality through its consciousness. Although that dictum was said in a theological context, it is also a beautiful and terse description of human knowledge and the position of historians and historical knowledge.

That is, consciousness becomes aware of the outside world only through sensory inputs. I cannot doubt the contents of my own consciousness, but let us remember that there is more than that impression reflected in the mirror of the mind. I can never doubt that it is my consciousness, it belongs to myself, and I am made aware of myself through my self-consciousness. This same consciousness makes sense of foreign natural forces or realities; like the electromagnetic force which touches and disturbs my eye’s retina as light photons, or the weak and strong forces of atoms as material, touchable, and sensible objects (either soft liquid or hard solid materials), and also gravity because of the inner ear’s sense of balance. They are not me, not myself, but foreign forces of reality/nature that affect me. Thanks to my consciousness, I am made aware of those natural forces as an alien reality that is independent and not related to my-self. Metaphorically speaking, our skulls/cranium resemble St. Jerome’s speculum. Let us suppose that the eyes are the doors of the cranium; then it also seems plausible to compare it with Plato’s Cave Metaphor. My consciousness and my Mind reside in the cranium of my head like a caveman; it senses only a very limited and weak part of some light spectrum which comes through the eye’s door. I can see only a dim light ray reflected in the mirror of my mind, or, let me say, on the walls of the cave. If only I could go outside the cave, then I would see a very different reality than the shadows on the wall of the cave, or reflected in my mind’s mirror. From this metaphor comes the discussion of the world of ideas and reality.

But can we leave the cave and go to see the outside world? My self or my mind cannot walk and go outside from the cave of its cranium/skull and make direct contact with reality. In this case, the mind is forced to make an inference from what it senses about reality, a second-hand, inferred knowledge about the alien outside world by using the mirror/wall of its consciousness, some impressions about reality as the reflected shadows on the wall of a cave. It really resembles Plato’s famous cave metaphor or St. Jerome’s dark mirror. I think Donald Hoffman’s metaphor of the interface is also very good; consciousness truly resembles the computer interface we see on a computer desktop. Consciousness is an interface or an illusion of reality created by the mind. *2

But then, if our consciousness is also a second-hand knowledge, what can we know directly about reality-in-itself? What do we know for sure? The only thing I cannot doubt is that I am conscious and also that consciousness belongs to me (it is not necessary now to speak about many different consciousness modes). That is, the most indisputable thing is not consciousness but rather the self-awareness attribute of that consciousness. According to the modern physicalist viewpoint of consciousness, even that self-awareness is also a construction of the mind. Sure, as a philosopher, I can doubt and debate everything. But if you do not accept the validity of selfhood, then there is no dependable or unsusceptible ground on which we can stand and debate with each other. In my judgment, that self-awareness is the most basic and undebatable identity principle. *3. There can be no logic without identity. Ego sum qui sum: I am that I am. That is a tautology that refers to itself with the identity principle, and all logical rules depend on identity. Anything is what it is! But our rational reasoning instruments also have their limitations and aberrations. I only mention here that, in my judgment, Logic, language, and math—these rational reasoning tools—also have their intrinsic paradoxes and limitations which we cannot eliminate easily.

All that we see or seem

Is but a dream within a dream.’ (E. A. Poe)

3. On the Limits of Language and understanding

As Wittgenstein once said: ‘Philosophy is a struggle against the language which is deceiving the mind’…*10 If only I could speak in large detail about all of these related subjects. I envy those ardent writers who wrote large volumes of books; and I say, ‘if only,’ because, even though I have already written some books about my own philosophy of history, they all remained as incomplete works, lacking some aspects of history here and there. Such an endeavor was a “never-ending story” that had never satisfied me. As it is said by Solomon in Ecclesiastes: ‘cunctae res difficiles non potest eas homo explicare sermone non saturatur oculus visuauris impletur auditu’: “All things are difficult and wearisome; Man is not able to tell it. The eye is not satisfied with seeing, Nor is the ear filled with hearing.” (Ecclesiastes I-8)

In short, every word is incomplete; man is not capable of speaking. *4.

Let us return to semantics and speak once again about language itself. I must articulate what I think about the capacity of human languages. Here, I will briefly mention my judgments about some general aspects of human languages.

For now, I will articulate some of my ideas as short, jurisdictive judgements: human languages are not capable of conveying truth, such as being a fully trustworthy description of living reality, because of the limits of not only human consciousness but also so many great flaws inherent in every human language. First of all, every language categorizes things according to its own historical development and its own grammatical construction; i.e., every language describes the passage of time differently. For example, Arabic grammar has only three different time tenses: past, present, and future (mazi, muzari, istikbal). Yet I remember, though I cannot recall the source of this saying now, once I had read that a scholar of Semitic languages said that Arabic language also has an ‘imperfect tense.’ Maybe it cannot be a grammatical tense but could be a way of telling an imperfect time tense with some descriptive phrases. Anyway, humans cannot understand Time perfectly; we do not even know “what is time,” so it is only natural that human languages have many different time tenses.

Let us remember that human languages are full of abstract, universal concepts. Humans could not think if there was not any universal concept, but let us again remember that all universals are dubious, just as every generalization is. Sure, I cannot discuss at length all the arguments of Platonists, Realists, Nominalists, or Conceptualists here, but universals do not really exist in the world extensionally. In addition, every human language is full of biased phrases, such as judgments of intensional logic, because of the conditioning nature of every human culture. Moreover, a judgment of intensional logic is not valid from the perspective of logic; but perhaps 80 percent of every human language is made up of these universals and so many biased phrases that are articulated with an intensional logic. Logical propositions should be expressed as extensional logic if they refer at all to a concrete thing. If so, then linguistic descriptions are always dubious because they always distort reality and mislead human thoughts and conduct.

Let us add that not only universals but every word of language might be considered deceitful because of distorting reality more or less; because a word can be only a representation of some reality, a word is merely a metaphysical symbol. As Semanticist Alfred Korzybsky put it: ‘The map is not the territory.’ Likewise, “the word is not the thing.” *5. To name something with a word does not necessarily imply that the referred thing, the named thing, really exists, either intensionally or res extensa. A name may designate a thing, and writing also metaphorically represents a thing. But a thing is not necessarily signified truthfully by a linguistic name, sign, or symbol. As Immanuel Kant put it: ‘the thing in itself cannot be known,’ we know only appearances (phenomenon). Let us also remember that there are many criteria of truth in philosophy, not only semantic or coherent theories of truth but also many others, such as correspondence theory of truth, and pragmatic, performative, sentential theories, etc. All in all, as Solomon put it in Ecclesiastes, cunctae res difficiles, non potest eas homo explicare sermone… All things are difficult and wearisome; Man is not able to tell it.

I wish to remind here the famous ‘regress argument’ of Sextus Empiricus:

‘Those who claim for themselves to judge the truth are bound to possess a criterion of truth. This criterion, then, either is without a judge’s approval or has been approved. But if it is without approval, whence comes it that it is trustworthy? For no matter of dispute is to be trusted without judging. And, if it has been approved, that which approves it, in turn, either has been approved or has not been approved, and so on ad infinitum.’* *6.

4. Some Additional Evaluations about Art, Science, Philosophy, Religion, and Mystical Experience

Art is art; it does not claim truth, but beauty and harmony. So art is free to create something whimsically; but again, history is something else, though it might be told in some art form of narration. A historian is not free to imagine historical events fictionally, unlike historical novels. History, in fact, is only a historiography; because the historical events themselves, which occurred in the past, cannot be known truly and satisfactorily even by the actors of those events. Let us imagine we have sufficient knowledge about some historical events, but could we articulate and describe those events of history as satisfactorily as, for example, Tolstoy’s War and Peace? I think that to describe the whole series of events and people as truly as that masterpiece exceeds even the capacity of the human mind. Unfortunately, only through dubious historical knowledge can one understand a little bit about humanity’s experience of the progress of events and their ultimate results. I will not speak more about History here, because I have already published my thoughts about the epistemology of historiography in a long article; so, I think it is enough to add that article at the end of this book as an annex for the more curious reader. (See Annex II.)

Then Science comes onto the stage, claiming that scientific subjects can be tested and, being so experimental, at least “inductively” shows that scientific claims are more trustworthy. Science is about the physical nature of matter, so it is all about the nature of conceivable dead matter. Whenever scientists wish to strengthen their scientific arguments theoretically, they use mathematics as far as possible, because mathematical formulas are provable; and because they depend on deductive reasoning, math is stronger than the inductive reasoning of scientific methods. Yet, ‘math is a first-class metaphysic’ (Oswald Spengler); that means, to strengthen theoretical physics, we use the metaphysical language of math, even though science tends to deny inconceivable metaphysical issues.

When it comes to Philosophy, first of all, it means theoretical thought, and now I remember Aristotle’s saying in his Poetics: ‘historia/history is all about unique special events and is not a suitable subject for making theoria; even poetry is more general than history.’ Philosophers make wonderful systematic theories of everything in a logically consistent way, but all their sayings remain within the scope of some semantic analyses of linguistic concepts. In my judgment, some magnificent philosophical systems might be very consistently constructed, but because they use simple two-valued Aristotelian logic as their reasoning instrument, they cannot touch and understand even physical reality. Because contemporary Quantum Mechanics of physics cannot compromise with that two-valued Aristotelian logic. As Heisenberg said in his book Physics and Philosophy, “the impossibility of the third option rule of logic does not apply in quantum mechanics.” That is, even the solid matter of microphysics cannot be comprehended by philosophy. Only the physics of daily life, i.e., Newtonian physics, is comprehensible by philosophers, but neither quantum mechanics nor cosmology. But philosophy is all about making consistent constructions of theories, though it is forced to remain in the semantic realms of language. Yet it teaches one how to think and how to doubt. Even though, because of the skepticism about old systematic philosophies, contemporary philosophy also tends to be analytical and epistemological instead of being synthetical, as meaningful philosophy should be. Yet ‘philosophical principles can only be understood in their concrete expression in history’ (Tolstoy). Without enough philosophical understanding, one tends to believe everything without doubt. That is why, without philosophical/dialectical maturity, one cannot think consistently and cannot doubt ideas even when it is surely necessary to question them. In short, Philosophy is absolutely necessary to make you alert in front of dubious issues.

For example, Latins say: ‘sapiens nihil affirmat quod non probet!’ (A wise person affirms nothing that they do not prove!). But as a very skeptical philosopher, I can doubt even mathematical proofs by questioning their fundamental axioms or postulates, simply saying ‘petitio principii!’ which means, ‘your fundamental principles as axioms or postulates need to be proven at first!’ If I do not accept the Euclidean axiom that ‘the shortest distance between two points is a straight line,’ though it seems very plausible and convincing to our eyes and consciousness, then the Euclidean proofs of geometry depending on that postulate collapse. That is why so many different geometries came into existence (Lobachevsky, Riemann, Poincaré, Hilbert geometries, and so on) beginning from the 18th century. In addition, though most mathematical reasoning depends on two-valued Aristotelian logic and is built on the consistency of mathematical reasoning, even math includes some reasoning problems like Cantor’s famous continuum hypothesis and Gödel’s theorem.

As for Religion or Theology, they are very important historical beliefs of human societies which bond individuals of society to each other as a strong instrument of social cohesion. Religion inspired people to act together to build civilizations; it was the reason and cause of many great historical events, so a good historian should respect religions. Grand theological explanations and constructions of a religion come into existence in time, but then this constructed theology and many different sectarian viewpoints of that theology can change or re-evaluate or sometimes reconstruct the history of its own religion. Since it is all about the history of that religion and its metaphysical beliefs, in time, it might become a very developed theological system and discusses all matters of humanity within its scope and methodology, sometimes logically inferring absolute results and judgments from the beliefs of the religion. Theological reasoning can make different interpretations of even core beliefs of religion for the sake of the consistency of a theological system. It seems meaningful to theologians if the discussed matter remains within the scope of those theological studies. But beliefs tend to be self-assured, and theologians are forced to speak according to a credo, so they speak as if their belief system is an absolute truth and can be proved logically. In fact, their arguments are only a debate, a reasoning style which uses only some inferences according to the rules of Aristotelian logic about the historical inheritance of a society’s beliefs (in Western Civilization and Islamic Civilization; other civilizations are something else). This is why I consider some historical accounts dubious when they depend on theological considerations. After all, a person or a society may believe anything, whether it is believable or absurd; belief is neither math nor science; theology is only a systematic knowledge of historical beliefs, so it cannot be proven. After all, it is possible to say “credo quia absurdum” (I believe because it is absurd) or, as St. Anselm says, “credo ut intelligam” (I believe in order that I may understand). As my readers should have noticed, I have raised very tough criticism even about mathematical proofs, arguing with the famous phrase ‘petitio principii’. This is why I consider some statements of historians and theologians as dubious statements; and so I do not wish to accept the theological implications of Kufic script at face value as true statements. Anyway, there are many different sectarian views of theological matters which are related to the history of the Qur’an.

There remains only Mystical Experience as a different claim of experiencing existence, in my classification of disciplines. If one has such an experience, it may convince them about the trustworthiness of some metaphysical experiences like Revelation (vahy) or other extraordinary metaphysical events. Mystical experience is not a normal daily life consciousness of humanity but an “altered state” of consciousness. There are many kinds of conscious states, and even pragmatist William James acknowledges that mystical experiences usually make a strong and permanent imprint on the person who experiences them, in his book The Varieties of Religious Experience. *7 And according to Henri Bergson, the religious beliefs of orthodoxy represent static religion as an establishment, but its mystical interpretation is a dynamical religion. Great artists and mystics are aware of the illuminations coming from spiritual realms, so they may have some more understanding about the claim of revelation such as the Qur’an. In any way, mystical experience is a different conscious state that is an intensive experience of reality compared to ordinary, waking life consciousness. But it is subjective; that is, this altered kind of consciousness is real only for the person who experiences it.

“Der Yemenî pîş-i menî, pîş-i menî der Yemenî”

→ “If you are in Yemen, you are before me; if you are before me, you are in Yemen.”

(The beloved’s presence transcends geography—being near in spirit is more real than physical closeness.If the beloved is truly present in the heart, even Yemen (a symbol of remoteness) becomes intimate.Conversely, if the heart is estranged, even physical nearness feels like exile.)

5, On History Itself, Historiography, and the Philosophy of History

Moreover, the history of Kufic scripture also is a convenient and perfect example to dispute the general nature of historical knowledge. Surely, it’s possible to discuss the role of historical knowledge, semantics, human knowledge, and beliefs in general. Yet, as I’ve already mentioned, if we adopt a holistic perspective, we could debate all related subjects about human destiny in this context too. After all, “In history, everything is related to everything else!”

In history, we don’t know what actually happened in the past; we know only historical documents and relics. Once, while speaking on history at ISAM (Islamic Research Center), I compared all historical remnants to the famous poetry of Imru al-Qays, “Kıfâ nebki min zikrâ habîbî ve menzili”: “Let’s stop here and cry, remembering the beloved and our hometown, the distance she passed through.” That is, all we possess are historical remnants; they are solely some relics of past events. Looking at them, we try to imagine those past events, just as Imru al-Qays imagines and remembers his beloved by looking at the relics of a camel caravan. Knowledge about historical remnants can be a science and could be investigated by scientific methods since they are existing material objects. This is the only truly scientific aspect of history. *8

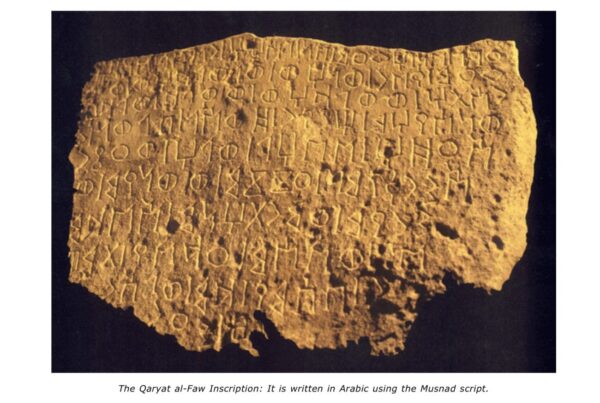

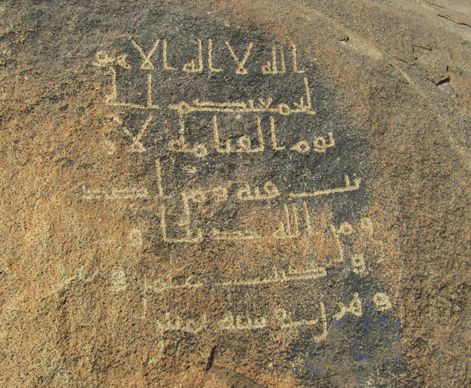

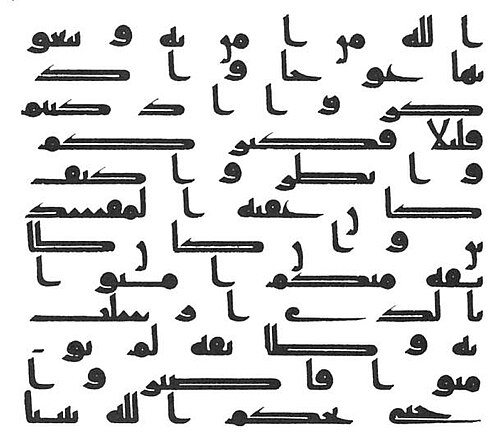

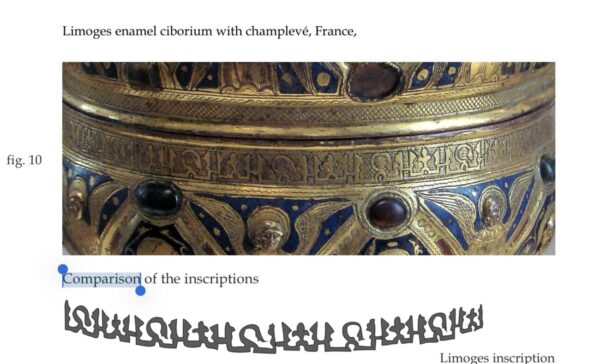

In fact, we don’t know for sure where Arabic script originated. There are only predictive arguments from Orientalists: some suggest it might come from the Nabataean script; others, that it might be a developed form of the Musnad script; still others guess that Arabic script was influenced by Syriac. There are even definitively different tendencies and preferences for one view over another, depending on different schools, such as French, German, or British Orientalist schools.

Indeed, Kufi script, Arabic script, and the history of Arabs in general are perfect examples of the dubious feature of all historical knowledge. As Will Durant beautifully articulated in his book, The Lessons of History: “To begin with, do we really know what the past was, what actually happened, or is history ‘a fable’ not quite ‘agreed upon’?” * Our knowledge of any past event is always incomplete, probably inaccurate, clouded by ambivalent evidence and biased historians, and perhaps distorted by our own patriotic or religious partisanship. Most history is guessing, and the rest is prejudice.” *9 Napoleon phrased it more wittily, which Will Durant probably alludes to: “What is history but a fable agreed upon!”

Carl Lotus Becker, a prominent American historian and political theorist, evacotively says that: “Since history is not an objective reality, but only an imaginative reconstruction of vanished events, the pattern that appears useful and agreeable to one generation is never entirely so to the next.” *1o Becker’s insight challenges the notion of historical objectivity, suggesting that each generation reshapes the past to suit its own needs and ideals

But history itself, as past events, has passed away and gone forever. What is known as historical narration is only a historiography, a story about past events of history according to historian`s imagination, which is what he infers to understand and narrate about past events based on interpretations of those relics. As Will Durant beautifully articulated in The Lessons of History: “Obviously historiography cannot be a science. It can only be an industry, an art, and a philosophy—an industry by ferreting out the facts, an art by establishing a meaningful order in the chaos of materials, a philosophy by seeking perspective and enlightenment. In philosophy, we try to see the part in the light of the whole; in the ‘philosophy of history,’ we try to see this moment in the light of the past. We know that in both cases this is a counsel of perfection; total perspective is an optical illusion. We do not know the whole of man’s history; there were probably many civilizations before the Sumerian or the Egyptian; we have just begun to dig! We must operate with partial knowledge and be provisionally content with probabilities; in history, as in science and politics, relativity rules, and all formulas should be suspect. ‘History smiles at all attempts to force its flow into theoretical patterns or logical grooves; it plays havoc with our generalizations, breaks our rules; history is baroque.’ Perhaps, within these limits, we can learn enough from history to bear reality patiently and to respect one another’s delusions.” *11

Once upon a time ı wrote an article about the forgotten dreams of Nebucadnezzar saying that events of the past times are like “forgotten dreams” emphasizing dream-like qualities of all human experiences. I will add that article as an annex to this essay. I will add two more articles written by me as annexes to this essay because I wish to expose my philosophy of history in a larger context than these short remarks and jurisdictive judgements; that is, in addition to the “forgotten dreams of Nebucadnezzar” you can read two more articles of me as annexes of this essay, “Man, Existence and Time” and “The Quest for Meaning throughout Time” too. Since ı am writing now, not only about kufi calligraphy but also about my phılosophy of history, for the curious reader, I also advice to see my book “The Essence of Existence” published by Amazon.

Then, historical knowledge about all the historical relics becomes dubious if historical understanding changes according to the historian’s interpretation and taste; therefore, it can only become an art or a philosophy of history. I have already written elsewhere about the epistemological value of historiography, in “The Quest of Meaning Throughout Time,” implying that historical narration is only a conjectural belief about some historical events:

“A historian has to imagine the flow of events in history, that is, how it could be possible that the river of events was formed and took a special river-bearing for the course of events that might have flowed. It is so hard to describe this awakened dream of consciousness—this self-deceptive imagination of the historian—that I cannot help but repeat that strong statement of the Antiquarian’s view of history, “sans aultre preuve que de simples conjectures dece qui pouvoit avoir este”: “it is only a guess, simply a conjectured belief without proof, since we can conceive that it was possible to occur (as implied by our imagination); then, presumably in any case, it really had happened so.” I will not repeat all of my epistemological analysis written in that essay but simply repeat one more paragraph from it:

“That is, a historical event could be, at most, an ‘imaginatively constructed and believed’ explanation of a historian. There remains only this ‘ratio credentis’: we might believe a historian on the basis of his professional authority.” *12

If so, what are the ends aimed at by historiography? And what could be the justifications of historiography? It is to narrate illustratively in a proper form what might have been discovered about history by the research and imagination of historians, as meaningfully stated by the aforesaid Antiquarian. And historians always try to write history as they imagine: that is, they try to change the past according to their wishful thinking and ideology. This is also a ridiculous and whimsical wish: they try to convince some people that their imagined version of the story of the past is definitely true. A historical evidence cannot provide any sufficient and necessary reason to prove that the indicated event is true, merely for the reason of being reported and described by it. Although it might seem strong evidence, there could be no ‘ratio veritatis’, no proven justification that ‘the event’ had actually occurred ‘as definitely as it has been told’ by that official document, witness, historian, or whatsoever. We can always suspect and deny its reliability.

As stated by Stephen J. Shoemaker: ‘Historians are rarely able to prove absolutely that something did happen, or did not happen, particularly for matters of great antiquity or when dealing with the formative history of a particular community, which is often a very active site of shifting memories.’ (C.K.P.38) *13*

‘Taking little bits out of a great many books which no one has ever read, and putting them together in one book which no one ever will read,’ quote Carl Becker. And there is a cynical saying, I don’t remember which historian said it: ‘history does not exist until a historian writes it.’

But actual historical events cannot be known even by those who experienced them. I will quote here from Carl Becker again:

“No doubt throughout all past time there actually occurred a series of events which, whether we know what it was or not, constitutes history in some ultimate sense. Nevertheless, much the greater part of these events we can know nothing about, not even that they occurred; many of them we can know only imperfectly; and even the few events that we think we know for sure we can never be absolutely certain of, since we can never revive them, never observe or test them directly. The event itself once occurred, but as an actual event it has disappeared; so that in dealing with it the only objective reality we can observe or test is some material trace which the event has left—usually a written document. With these traces of vanished events, these documents, we must be content since they are all we have; from them we infer what the event was, we affirm that it is a fact that the event was so and so.”(Excerpted from this website) * 14

In fact, what we know about the history of Arabs, Arabic script, Prophet Muhammad, the Qur’an, and all other stories related to the first century of Islamic History is all secondhand knowledge inferred from the traditional hearsay of historical sources and relics, which are not contemporary with Prophet Muhammad but are remnants from the second and third centuries of Islam. We do not have any authentic relic that was contemporary with Prophet Muhammad. Of course, we cannot know the actual series of historical events. History in itself cannot be known; historical knowledge is something else, as historiography, an art form which is a narration of past events as imagined—gathered information which depends on all kinds of historical sources—and told by a historian. This is why Voltaire cynically says: “little bit more than what is said by a scriber to another script.” Suppose we had satisfactorily enough and true knowledge about the flow of historical events; are we sure that we could understand the essence of living reality by some descriptive narration? In history, we can never be sure of the truthfulness of statements made by a contemporary observer of events or written by a historian about an event; it cannot be proven like mathematical statements and obviously cannot be tested like scientific materials. Anyway, an art of narration might be beautiful but could not claim that all its statements are true. Here again, for the sake of clarity, I am forced to show my classification of disciplines, at least in short, to explain my highly skeptical attitudes towards matters related to Kufic scripture, its history, and some linguistic, philosophical, and theological implications of the subject. As quoted from a poet by Aviezer Tucker in his introduction to A Companion to The Philosophy of History and Historiography: Perhaps we are…

‘Still in the earliest days of history

When the world existed only in theory . . .’ *15

chapter three

1. On Historical Origins of Arabic Script and Historical Development of Kufi Calligraphy

Naturally, I’ve already seen many well-written books on the paleography and epigraphy of Arabic script by famous Orientalists. I’ve also read many books, even some manuscripts, by Arab, Persian, or Turkish writers. However, I do not see a necessity to repeat all the knowledge I’ve learned from those books—all the known and unknown and problematic aspects of the subject. Instead, I’ll offer my interpretations whenever it seems proper to me. Nevertheless, this essay will include a large enough bibliography for the more interested reader who wishes to learn more.

Let us recall some historical knowledge about the Arab people and the Qur’an: According to the Muslim religion, the Qur’an is the word of Allah revealed by the archangel Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad. According to the traditional geneology prophet Muhammed`s ancestors descended from Abraham`sson ishmael. And Arab people also are divided into two groups: Adnani (northern Arabs considered Arab i-musta`ribe—that is, “Arabized Arabs” descended from Ishmael)—and Qahtani (southern Arabs, like the Yemenis).This is why the Arabs are called ‘The sons of Ishmael’ by the Jews. According to the Old Testamen, Abraham and Hagar’s son Ishmael had ten children. The names of Ishmael’s first and second sons given by the Old Testament seemed interestingly historical to me because it is referring Nabatian and Kedar kingdoms. Nebaioth, the firstborn of Ishmael, and Kedar. `Now this is the genealogy of Ishmael, Abraham’s son, whom Hagar the Egyptian, Sarah’s maidservant, bore to Abraham. 13 And these were the names of the sons of Ishmael, by their names, according to their generations: The firstborn of Ishmael, Nebajoth; then Kedar, Adbeel, Mibsam, 14 Mishma, Dumah, Massa, 15 [a]Hadar, Tema, Jetur, Naphish, and Kedemah. 16 These were the sons of Ishmael and these were their names, by their towns and their [b]settlements, twelve princes according to their nations.` *1. Kedar is the Father of the Qedarites, a northern Arab tribe that controlled the area between the Persian Gulf and the Sinai Peninsula. According to tradition, he is the ancestor of the Quraysh tribe, and thus, ancestor of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.*2 According to Old Testament Nebaioth was the Father of Nabataean people and according to paleographic and epigraphic investigations by Orientalists, the most widely held guess among them is that Arabic script originated from the Nabataean script.

The origins of the Arabic script have been a subject of scholarly debate for centuries. There are two main theories about its origins: the Nabataean Theory and the Musnad Theory.

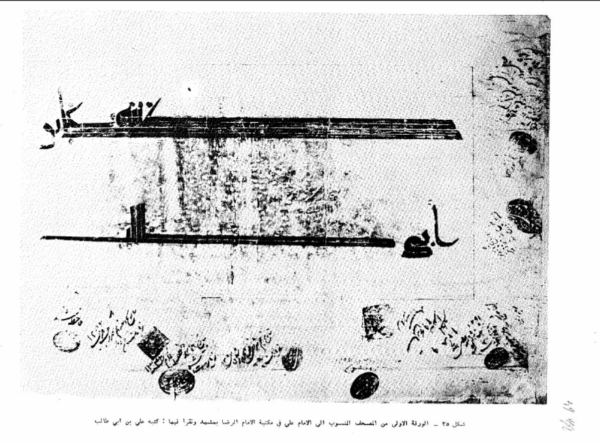

For example, Irvin Cemil Schick states: `The old and generally dominant view is that Arabic script was derived from Nabataean script; however, the chronological gap between the Nabataean and Arab civilizations necessitates a reexamination of this view. In more recent times, an alternative theory has been proposed suggesting that Arabic script originated from Aramaic/Syriac script. The former view has found support in Anglo-Saxon academic circles, while the latter has been favored in French scholarly environments. It would be highly appropriate for these theories to be discussed in Turkey as well. Yet, this issue—pertaining to the pre-Ottoman Turkish era—has remained off the agenda to this day, like many other “foreign” topics. Only legendary accounts, rather than historical evidence, have appeared in Turkish sources—stories passed down from generation to generation claiming that writing was invented by Prophet Adam or Prophet Idris, and that the first calligrapher was Imam Ali. ` *5

The most widely accepted theory is that the Arabic alphabet evolved from the Nabataean script, which itself was derived from the Aramaic alphabet. This evolution followed this path:

Phoenician alphabet → Aramaic alphabet → Nabataean Aramaic → Nabataean Arabic → Paleo-Arabic → Classical Arabic → Modern Standard Arabic

* 6 .wikipedia,

Alain Gerge says “The Nabataean origin of the Arabic script has only been decisively established in recent years thanks to the discovery of a growing number of transitional late Nabataean inscriptions, especially in Saudi Arabia. For much of the twentieth century, a strand in scholarship had instead posited a Syriac origin of the script. *7

*8

The Nabataean script was used by the Nabataean Kingdom, centered in Petra (in modern-day Jordan) from around the 3rd century BCE. The Nabataeans were predominantly Arab Semitic tribes living in the area, controlling trade routes from the eastern Mediterranean shores to Hijaz (Saudi Arabia) and Yemen. A transitional phase between the Nabataean Aramaic script and a subsequent, recognizably Arabic script, is known as Nabataean Arabic. The pre-Islamic phase of the script as it existed in the fifth and sixth centuries CE, once it had become recognizably similar to the script as it came to be known in the Islamic era, is known as Paleo-Arabic.

An alternative Musnad Theory suggests that the Arabic script can be traced back to Ancient North Arabian scripts, which are derived from the ancient South Arabian script (Arabic: khaṭṭ al-musnad).

*9

`This hypothesis has been discussed by Arabic scholars Ibn Jinni and Ibn Khaldun. Some scholars, like Ahmed Sharaf Al-Din, have argued that the relationship between the Arabic alphabet and the Nabataeans is only due to the influence of the later after its emergence (from Ancient South Arabian script). Arabic has a one-to-one correspondence with ancient South Arabian script except for one letter. German historian Max Muller (1823-1900) thought the Phoenician script was adapted from Musnad during the 9th century BCE when the Minaean Kingdom of Yemen controlled areas of the Eastern Mediterranean shores. Syrian scholar Shakīb ´Arslan shares this view. *1o

Thus, to explore the history of the Kufic script is not merely to trace the formal evolution of a writing style. It also raises critical questions about historiography and epistemology. The origins of writing, its transformations, the contexts of its use, and the aesthetic choices it entails are shaped not only by material evidence but also by historical assumptions, intellectual frameworks, and interpretive narratives.

That is, historical origins of the Kufic script are not limited to the linear evolution of the Arabic script; they also reflect a broader cultural, political, and theological transformation. The development of Kufic writing corresponds with a rapidly evolving epistemological and aesthetic quest in the wake of Islam’s emergence. As a script, Kufic embodies the early Muslim community’s dual concern: preserving the Qur’anic revelation with precision and imparting to it a form of solemnity and visual dignity.

Because I do not wish to write a large book volume about the paleography of Arabic script, like many Orientalists have done before me, I will only mention here some good sources—which are easily reachable on the internet—about the history of Arabic people, Arabic inscriptions, Arabic script, and Kufic scripture, etc.

One can find many examples from the Nabataean script and other Arabic inscriptions discovered by archaeologists on internet sites. There are some websites on the internet that show all the Arabic inscriptions and scripts, including new archaeological discoveries, such as:

- Digital archive for the study of pre-Islamic Arabian inscriptions: https://dasi.cnr.it/

- History of the Arabic alphabet – Wikipedia

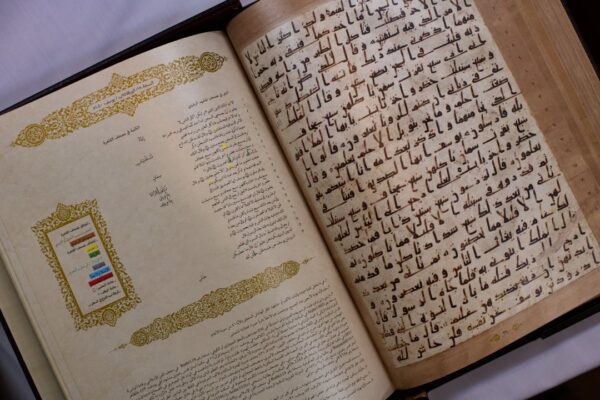

- https://corpuscoranicum.de/en

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Arabic_inscriptions

- https://www.islamic-awareness.org/history/islam/inscriptions

- The Qur’anic Manuscripts In Museums, Institutes, Libraries & Collections

Rather than conveying all the historical information I’ve gathered from the books of Orientalists and Muslim scholars, I wish to interpret certain aspects of Kufi scripture as they relate to various differing perspectives, whenever it seems imperative to do so.. For instance, we possess numerous historical relics of Arabic scripts—inscriptions, papyri, manuscripts written on parchment, and later, coins minted by Umayyads, as well as buildings like the Dome of the Rock, which is ornamented with Kufic calligraphy.

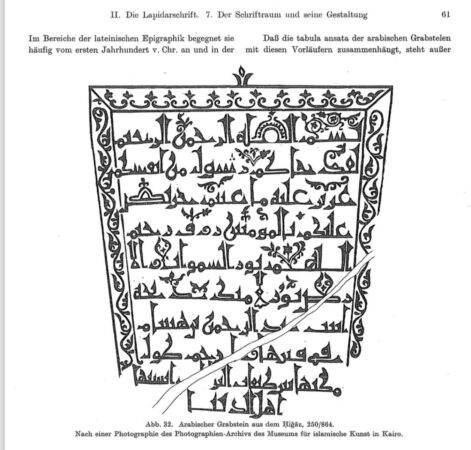

Indeed, the Kufi style, as anyone who has seen it can tell, is perfect for stone inscriptions – its simplistic, angular, and overall lapidary nature make it so.