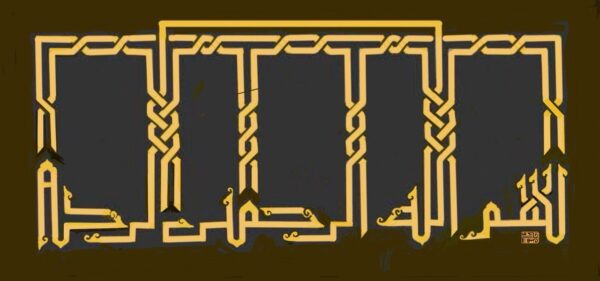

kufi calligraphy: the sacred script

اِقْرَأْ بِاسْمِ رَبِّكَ الَّذٖي خَلَقَۚ

,خَلَقَ الْاِنْسَانَ مِنْ عَلَقٍۚ

اِقْرَأْ وَ رَبُّكَ الْاَكْرَمُۙ

اَلَّذٖي عَلَّمَ بِالْقَلَمِۙ

عَلَّمَ الْاِنْسَانَ مَا لَمْ يَعْلَمْؕ

Qur’an /Alak

Recite: In the name of thy Lord who created

Created man of a blood-clot.

Recite: And thy Lord is the most Generous,

Who taught by the Pen

Taught Man,that he knew not

Qur’an/ The Blood-clot (1)

وَعَلَّمَ اٰدَمَ الْاَسْمَٓاءَ كُلَّهَا

And He taught Adam the names, all of them

Quran/ The Cow 31

Ma’nâ yı-kelâm şâhid i-mazmûn i-Hudâdır

Gönlüm sadefinden olur azrâ gibi peydâ

“The meaning of the word professes

the hidden existence of God in it”

This word, likewise a virgin pearl,

occurs in my heart which is the mother-of-pearl.”

Şeydâ Dîvânı, Tevhid Kasidesi

.سم الله الرحمن الرحيم

الحمد لله الذي خلق القلم أولاً و كتب الكتاب المكنون بذلك القلم في اللوح المحفوظ . و فيه كتب كل المقدّرات، من البداية إلى يوم القيامة. هو الله الخالق لكل أمرٍ و شأن. و الشكر لا يعد لمن خلق الإنسان و علّمه البيان . و هو علّم آدم الأسماء كلّها، و علّم بالقلم ، و علّم الإنسان ما لم يعلم . لأن الوحي الأوّل كان اقرأ باسم ربّك و قيل في تلك الآية هو الذي علم بالقلم

.كما كان هذا القسم بالقلم في القرآن, ن و القلم و ما يسطرون

…و في القرآن له آية تدل على ماهیت القرآن. بل هو قرآن مجيد في لوحٍ محفوظ

صلوا على محمّد هو كشف الدجى بنور الوحي و نوّر قلوب العارفين به . و بدأ الخط الكوفي في عصره ليكتب آيات القرآن ولقد كان القرآن مصدر الفكر والحضارة الإسلامية كلها. والقرآن كتب بالخط الكوفي لعدة قرون. ولهذا السبب أصبح الخط الكوفي أشهر في تمثيل الحضارة الإسلامية. كما كان الان . وهذا من فضل ربي

In the name of God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful

Praise be to God who created the Pen first and the hidden book was written with that pen on the Preserved Tablet. In it are written all the decrees, from the beginning until the Day of Resurrection. He is God, the Creator of every matter and phenomen. Countless Gratitude is to the One who created man and taught him speech. He taught Adam all the names, taught with the pen, and taught man what he did not know. Because the first revelation was “Read in the name of your Lord,” and it also was said in that verse: “He is the one who taught with the pen.” As this oath was in the pen in the Qur’an Nun, by the pen, and what the lines it writes…And in the Qur’an there is a verse that indicates that qur’an is eternal. But rather it is glorious Qur’an in a preserved tablet.

Pray for Muhammad, he removes darkness with the light of revelation and enlightens the hearts of those who know him. In his era, the Kufic script began to write verses of the Qur’an, and the Qur’an was the source of all Islamic thought and civilization. The Qur’an was written in Kufic script for centuries. For this reason, the Kufic script became a representation of Islamic civilization. As it was now. This is from the grace of my Lord.

In what manner silent letters of the kufic script has become a resonant spectrum of islamic culture?

A Philosophical Perspective on Writing, Human Knowledge, History And Historical Significance of the Kufic Script:

Sacred Text, Revelation, and the Ontology of Writing

The nature of writing kûfî calligraphy goes beyond to its material structure or symbolic letters; because it was the materialized face of the sacred word, manifested face of the sacred revelation of Qur’an. because Qur’an’s mediating role between the human heart and Allah, that is the soul of Qur`an had been embodied by kufic sript. According to Qur’anic revelation, writing is not merely a record but a manifestation—an embodiment—of divine knowledge. As it is expressed, in the aforementioned epigraph, in the very first verses of the Qur’an;

“Recite in the name of your Lord who created—

Created man from a clinging substance.

Recite, and your Lord is the Most Generous—

Who taught by the pen—

Taught man what he did not know.” (Qur’an, 96:1–5)

The pen (al-qalam)’ as described in this verse by Qur’an, is not only an instrument of writing but of divine instruction. Here, the Pen is not only a tool but a sacred symbol that records knowledge foreseeing to become alive later, to come into the act of creation.

In fact, Qur’an instructs to begin with God’s name and commands human beings to learn, to read, and to pursue knowledge. It is an interesting mixtum compositum that creation, knowledge, and writing mentioned all together in the first verses of Qur’an. Human existence, the capacity for learning, and the act of writing are intertwined in a singular ontological structure here. And the name of revelation, The Qur’an itself, means ‘to be recited’; that is, meaning itself is revealed in the heart of the words and apparently materialized and represented as kufic script’ and then become alive when it is recited as Qur’an.

This ontological framework highlights here the metaphysical question of representation—how truth is made manifest. Here, the Qur’anic concept of the Lawḥ Maḥfūẓ (Preserved Tablet) becomes pertinent. The Qur’an itself, as a timeless text, is said to be inscribed on the eternal tablet:

بل هو قرآن مجيد في لوحٍ محفوظ

“Indeed, it is a glorious Qur’an,

In a Preserved Tablet.” (Qur’an, 85:21–22)

Here, The Lawḥ Maḥfūẓ is understood as the cosmic ledger of divine decree, destiny, and knowledge. In this context, writing is not merely a communicative tool but a metaphysical register. The transcription of the Qur’an into written form does not reduce its timelessness; rather, it translates the eternal into the human realm of comprehension. Here, kufic script serves not only ontological but also a theophanic function.

Islamic scholars have addressed these themes across theological, linguistic, and philosophical dimensions. Linguists such as Ibn Fāris and Ibn Jinnī maintained that language and writing possess a divine origin, grounding this belief in the verse:

وَعَلَّمَ اٰدَمَ الْاَسْمَٓاءَ كُلَّهَا :

“And He taught Adam the names—all of them…” (Qur’an, 2:31)

Indeed, according to Qur’an, human language also had been taught to Adam by God; according to this verse, language is not a conventional communication instrument made by men.

This verse does not refer solely to vocabulary acquisition but also to the naming of meanings, concepts, and even realities. Accordingly, writing is not simply a human invention but part of the ontological continuity of divine instruction—a vehicle of revelation, an embodiment of meaning, and a visible form of truth.

اِقْرَأْ وَ رَبُّكَ الْاَكْرَمُۙ

اَلَّذٖي عَلَّمَ بِالْقَلَمِۙ

Recite: And thy Lord is the most Generous,

Who taught by the Pen

Taught Man,that he knew not

Qur’an/ The Blood-clot

Writing, in this view, is not a creation but a tajallī—a divine manifestation.

It is believed by orthodox (sünnî) muslim that Qur’an is the word of God brought by Gebrail to the consciousness of Muhammad and being so, Qur’an is the incarnation of the word of God and has no beginning in time likewise the guarded scripture (levh’ mahfuz).

Because of this levh-i mahfuz, which is a metaphysical guarded book and includes all the events from the beginning until doomsday, naturally a theological problem would arise: Predestination. In that case, is there a free choice of human volition? If it is the word of God brought by Gebrail to the prophet, is this word, the Qur’an is created in time or not? Because it is revealed from what God who created before everything else the Pen/kalem and the guarded book/levhi mahfuz. Even the name of revealation, “Qur’an” means reading aloud, Reciting, the name does not designate a book in usual sense. Perhaps ıt could be understood as reciting some verses of Lewhi Mahfuz as revealed to prophet’s conscıousness. And what about the nature of revealation as a mystical experience of Prophet . As an altered state of conscıousness? How and why he organized his believers to establish a ‘theonomous order’ which tied them by both faith and politics. Why Qur’an does not have a usual book format and why prophet did not ask from his ‘clerks of revealation’ to write down all the verses of the Qur’an regularly in a book format. All these questions and many similar questions also are discussed by many sectarian theologians beginning from the first century of Islam. Why Language and even Writing are regarded as not created by men but given to Adam according to some medieaval islamic scholars?

For example , ibn al-Faris says that, ‘no doubt the script is not an artwork (sun’u) of humanity’, it is not man-made. And according to Qalqashandi, arabic letters also are revealed to Adam or prophet Hud’.

According to this view, writing is not merely a tool of communication but an extension of revelation and contemplation. It is the visual embodiment of the divine attribute of speech (kelām).

If writing stems from a divine source, then letters and symbols do not simply signify meaning—they embody and transmit it. Each grapheme becomes a theophany, not merely a sign. Alternatively, if writing is a human construct, then letters and symbols are arbitrary indicators whose meaning is produced through consensus and context.

Muhammed Antakî says in his book ‘el Vecîz fî Fıkh ül-Lüga’(p.25-27) ‘because of the above-mentioned verse of the Qur’an, ‘He taught Adam all the names (وَعَلَّمَ اٰدَمَ الْاَسْمَٓاءَ كُلَّهَا), some muslim scholars say that the language itself is not created by men but taught to Adam by God (Tevkîfî) and according to some other muslim scholars -who also speak quoting another Qur’anic verses; language came into existence culturally made by men ( bi’t-tevatu).

Within this Islamic intellectual tradition, this inquiry has largely revolved around the question of whether language is of divine origin (tawqīfī) or a human invention (isti‘lāḥī or taʿātī); yet, this issue is not merely a philosophical curiosity but an epistemological question that directly informs the meaning of writing itself—especially sacred writing in Arabic—and, by extension, the semantic depth of the Kufic script.

According to Muhammad Antaki, such debates are not exclusive to Islamic thought. In Western philosophy, too, the same question arises. The quest for the origin of language begins in ancient Greeks with this question: ‘is a name’s designation to the reality of a thing is created by men with convention (tevatu) or comes from the nature of man’ (is it taught by God to Adam?) According to Heraclit, language/logos is not made by men; that is, the name signifies the the named thing naturally. according to Democritos it is made by men; language also, likewise all other man-made elements of culture, made by conventions between people.’ Plato’s Cratylus famously stages the conflict between the view that names are “natural” (phýsei) and the view that they are conventional (thései). Do names reflect the essence of things, or are they arbitrary? This remains a central concern in modern philosophy of language. While Plato leans toward the idea that some names may be inherently appropriate, the nominalist tradition would later dominate Western discourse. Thinkers such as John Locke, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Saul Kripke reconceived the relationship between words and meaning through frameworks of mental representation, social usage, and linguistic practice. This dispute goes on in western philosophy until now but it is not necessary here to quote what more western philosophers say about this matter.

As transmitted in the book ‘Fıkh ul-Luga’ (semantics), İbni Faris says that Arabic language is tevkîfî (god-given) according to the aforement’ned verse of the Qur’an that states God taught to Adam all the names. Ibni Faris does not only give this kind of evidence (naklî) which is based on Qur’an verses, but also make a reasoning (aklī) evidence that, “ because we do not know any example of giving a name to something by the people who lived in the recent past, also we did not hear that companions of prophet has made new names or terms…” Yet the majority of muslim scholars say that `origin of the language is tevatu’(by convention) and language is istilah (terminology); it is not made by ilham, vahiy (revealation) or tevkîf (God-given)’. For example, Kadı Ebubekir el Bâkıllânî says that both are possible: “inne t-ta’lim kad husile bi’l-ilhâm ey bi’l kuvveti, lekad vadaa allahu fi’l-linsân meleketü’l halk, sümme terekehu yahluku alâ hevâihi” which means “Adam learned by reveleation, that is the language is God-given or God gave to man ability to create and leave him to create as he wish”. Abū Bakr al-Bāqillānī and some other scholars also argued that writing developed gradually as a product of social convention and human intellect. According to this view, writing arises not from a sacred origin but from rational necessity and human adaptation. It is not tawqīfī (divinely fixed) but ta‘ātī (emergent from mutual human exchange).This dichotomy over the origin of language has profound implications for the relationship between writing and meaning.

Indeed, this is a universal philosophical question about meaning and representation.

This is a difficult subject in semantics and I know it can not be expressed in short with some few and simple statements. For example, Saul Kripke has made large semantical and logical discussions about ‘naming’ in his book ‘Naming and Necessity’. I will mention here these contemporary logical and semantical arguments about naming merely making an interesting excerpt from Saul Kripke:

‘Sometimes we discover that two names have the same referent, and express this by an identity statement.so, for example, you see a star in the evening and it’s called ‘Hesperus’ (evening star). We see a star in the morning and caal it ‘Phosphorus (morning star). Well, then,in fact we find that it’s not a star, but is the planet Venus and that Hesperus and Phosphorus are in fact same. So we express this by ‘Hesperus is Phosphorus’…Also we may raise the question whether a name has any reference at all when we ask, e.g.,whether Aristotle ever existed… what really is queried is whether anything answers to the properties we associate with the name-in the case of Aristotle, whether any one greek philosopher produced certain works, or at least a suitable number of them.`

Kripke’s famous example—the dual naming of the planet Venus as Phosphorus (morning star) and Hesperus (evening star)—exemplifies the complexity of reference and naming. Although the two names refer to the same celestial object, their different usages suggest distinct epistemic paths. This complicates the question of whether writing merely reflects reality or actively constitutes it. The act of naming—and by extension writing—is not merely descriptive but generative of meaning.

In fact it is possible to discuss in this context Leibnitz law of identity, `identity of indiscernibles`, but I do not wish to delve into all the philosophical implications of Qur’anic verses, yet I have to say that words or names may imply more than its apparent meaning. Words or names may imply much more difficult problematic philosophical matters than it has been understood by their traditional usage in the language. And so, sometimes they even transcend the capacity of human reasoning. I do not wish to debate here any human belief, so I will not discuss here Leibnitz’s law; but I suspect that, if I could dispute in large context this idea of “identity of indiscernibles” of Leibnitz; in that case, not only naming but even the identity of the named things could seem dubious. Let me remind here that identity is the first principle of logic, i.e. “a thing is what it is”, other rules of logic also derived from this identity principle; and being so, all human reasoning depends on identity principle. The most satisfactory statement of identity was indeed, “ego sum qui sum”, which is said to Moses on the Mount Sinai according to Old Testament. Yet scholars, especially some theologians, do not know that human knowledge, language and reasoning capacity of humanity are not capable of answering satisfactorily every problem of truth we have come face to face. As beautifuly stated by Hallâc: “Truth is true only for itself!”

That is, within Islamic thought, these philosophical concerns converge on writing. Kufic script, in this regard, is not merely a stylistic choice but a material manifestation of the sacred ontological and theological dimensions of writing. It is not meant only to be read but to be contemplated, visualized, and intuitively grasped.

But I do not wish to discuss those names ‘Qur’an (recitation), Kitabu meknûn/Levhi mahfuz (kept and guarded book) with all of the historical and theological implications of these names; i.e., predestination/fate problem or the role of man in the actions of historical events. After all, this is an essay about the calligraphy of kufi, not particularly theology or the “sacred scripture Qur’an itself”.

Thus, in the early centuries of Islamic civilization, Kufic script emerged not only as a mode of writing but also as a metaphysical structure through which the sacred was represented. It serves as a conduction channel for transferring revelation into spatial and temporal registers. It is the symbolically embodied aspect of articulating metaphysical truths as revealed by Qur`an.

Thus, the usage of Kufic script in the earliest Qur’anic manuscripts enabled a strong identification between the form of writing and the content it carried. Within this framework, geometric composition of the script might be perceived as a visual symbol of divine mystery. Its symmetrical balance of vertical and horizontal lines seems like the divine order embedded in the universe. The space between letters, the proportional heights and widths letters, were functional features—but they also became revered as part of a sacred style that reinforced the sanctity of the message.

Let me remind here Ibn al-ʿArabī’s theory of the “ontology of letters” which is especially illuminating. According to Ibn al-ʿArabī, every letter is a theophany—an outward manifestation of one of the metaphysical realities contained in divine knowledge. Letters are not accidental phonetic tools; they are expressions of divine being. Writing becomes a surface upon which these theophanies appear. The fixed geometric nature of Kufic script shows its ontological and metaphysical charge more visibly potent.

Ibn al-ʿArabī says: “All praise be to Allah, who instills meanings into the heart of words.” For Ibn al-ʿArabī, all letters are symbolic representations of God’s creative act. A letter is not merely a sound unit but the primordial shape of a being. Ibn al-ʿArabī’s theory of letters elevates this discussion to a mystical plane. In his thought, letters become the metaphysical building blocks of existence, each reflecting an aspect or attribute of the Divine Names.

This idea again resonates in the mystical dictum of al-Ḥallāj:

“Letters are bodies, and meanings are their souls.”

As if, the architectural form of Kufic script embodies a belief that letters carry a metaphysical essence. Kufic calligraphy solemnly displays and suggests the aesthetical and visual expression of this reverence for the sacred words.

These theological implications of Kufic script is not confined to the shapes of letters alone. The materials with kufi inscriptions or the space it occupies like mihrab, also contribute to its semantic richness. Qur’an verses written in Kufic script are not only vehicles of oral transmission but served also as visual representations of divine revelation. Some Qur’anic verses in Kufic script were often integrated into architectural surfaces—thus making revelation to merge with space and amplifying the symbolic power of the script.

This intermingling of writing with cosmic order is implied by Qur’anic verses such as the opening of Sūrat al-Qalam:

“Nūn. By the pen and what they inscribe.” (Qur’an, 68:1)

Here, The Pen is not an ordinary object but as aforementioned it is the first creation of God, inscribing divine decree and order into existence. Hadith traditions also affirm this interpretation, stating that the first thing God created was the Pen. Here, writing signifies not only knowledge production but also the act of inscribing destiny and existence.

Kufic calligraphy, according to this cosmological symbolism, seems both static and dynamic. It seems majestic and static in its geometric fixity; but also dynamic because it embodies revelation and continually acquires new layers of meaning in time. Its static form suggests permanence, but its dynamic semiotic potential emphasize the timeless relevance of the sacred message.

Moreover, the structural design of Kufic script could imply a reverence for an aesthetical feeling which aligns closely with the Islamic concept of tawḥīd—the oneness and unity of God. Its repetitive, proportionate, majestic visual character commonly used on important buildings makes Kufic calligraphy an aesthetic affirmation of divine unity and also an identity symbol of Islamic civilization. Each letter occupies a specific place in this visual cosmos; nothing is arbitrary. In such a way, Kufic script becomes a visual and symbolic articulation of tawḥīd at both the formal and conceptual levels.

It really occupies a distinctive position within this representational framework.E.g., its geometric construction produces a space where form and meaning meet. Its solemn and majestic abstraction invites not only textual reading but also intuitive contemplation. Kufic does not assert meaning directly; it intimates, alludes, and beckons the observer toward a metaphysical horizon.

As if, Kufic script visually expresses the belief that letters are not just phonetic units but ontological entities. Al-Ḥallāj’s dictum –“Letters are bodies, meanings are their souls”- resonates here as a metaphysical hermeneutic.

Kufic script, then, does not merely transcribe a text—it transmits the very structure of its meaning. The ratios between letters, their symmetrical layout, recurrence, and internal logic are not simply visual choices but they reflect an architecture of meaning. Kufic is simultaneously a bearer and producer of meaning, an aesthetic system through which ontological truths are encoded.

This understanding of Kufic calligraphy marks it as a unique expression of the Islamic conception of the relationship between writing and truth. While preserving sacred content, it also suggests that meaning is not static but always subject to reinterpretation. Kufic’s formal rigidity offers a visual anchor through which shifting interpretations may gain stability.

In conclusion, debates over the origin of language and writing are not merely historical but ontological and epistemological in nature. Kufic calligraphy stands at the center of this discourse: it embodies the sacred, provokes reflection on meaning, and channels metaphysical resonance. In the silence of its letters, one hears the echoes of a vast cultural and theological vision. It is not just a calligraphy—it is a metaphysical architecture, a form of thought, and a sanctuary for meaning.

This is why the versatile symbolism of Kufic script, appears so often in Islamic architecture. It usually adorns domes, mihrabs, or arches, so Kufic becomes as an act of devotion, contemplation, and transmission of knowledge. Kufic inscriptions of sacred texts onto architectural surfaces show within this uniformity of style that space itself becomes a symbol of tewhid (unity of Allah), a bearer of the unique meaning and identity of Islamic civilization.

That is, Kufic script manifests the integral interrelationship among knowledge, revelation, destiny, and aesthetics in Islam. Its geometric form implies cosmic order; its metaphysical dimension transforms letters into symbols of being. Kufic calligraphy is not merely writing—it seems as if it is the embodiment of theological truth and a sacred way through which the unseen is made visible.

On the other hand, there is a striking similarity between levh- i mahfuz /guarded plate/ preserved plate (which Qur’an also means reciting some of the verses from that guarded book revealed by archangel Gebrail to prophet Muhammed’s heart) and contemporary simulation practice. As if, this writing act resembles the contemporary practice of writing some algorithm codes of a computer-game which later comes into play whenever you wish to play that game. Indeed, those verses of Qur’an about the guarded tablet (levhi mahfuz) reminds me some contemporary discussions about whether this universe, the existence, is real or a simulation or what not. As it is known, some virtual reality games are only written algorithms, they are written by a code-script and it becomes alive to be seen and played in computer games on a screen. Nowadays some physic theorists seriously argue that universe could be a simulation written and played likewise those virtual reality games. Sure, it could be thought so, metaphorically or seriously; and it is interesting to see that what Qur’an describes as Pen and Guarded Scripture (levhi mahfuz) articulates exactly the same idea: God created Pen and the pen wrote every events from the beginning to the doomsday. That is, like a virtual game, what happened in this universe is written/ or coded and predestined in that guarded book (levhi mahfuz/kitabu meknûn) and then all events happen according to the codes of that guarded-book which means our universe is only a simulation, there should be a real existence but this world is not real; it is just like a virtual game, a virtual reality.

Anyway because of the belief about above-mentioned levhi mahfuz/guarded book, same simulation metaphor used by a Turkish poet too. I will include the calligraphy of Neyzen Tevfik poem also which says:

Yazılmış alnına her neyse fi’liin, reddi nâkaabil

Hüner, bu defter-i âmâl-i ömrü hoşca dürmektir

Musaddaktır bu î’lâm tâ ezelelden muhr-i hikmetle

Cihâna gelmeden maksad bu tatbikâtı görmektir”\

“Whatever is written on the forehead of the deed, its rejection is impossible

Skill is to neatly fold this book of life’s deeds.

This declaration is confirmed with the seal of wisdom from eternity.

The purpose for coming into the world is to witness these practices.

We know already from neurophysiology and consciousness studies that, what we know as the world or existence, is a simulated picture made by human consciousness. As metaphorically explained by Donald Hoffmann, human consciousness is like a computer interface which is a simplified but useful description of the world. I remember here Edgar A. Poe’s beautiful poem which he says: